Until now, MDMA has mostly been studied in the context of treating PTSD and helping with autism. Psychiatrist Ben Sessa is now conducting the world’s first clinical study using MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to treat alcohol addiction, at the University of Bristol. According to him MDMA can be effective to treat addiction issues, because it “brings a particular emphasis on empathy and connection with the positive, loving part of the self, and that’s why it’s good for trauma.”

You often say that 2/3 of people with addictions have been traumatised or abused. Do you think there is addiction without trauma?

It depends on how you define trauma. There’s what I call ‘big T trauma’ and ‘little t trauma’. Not all people with addictions have suffered severe physical or sexual abuse. But if you ask people what was their experience of childhood, a vast majority of them will say it was cold: they didn’t feel loved or wanted, their parents weren’t really there for them. Those experiences fit in with what you’d call emotional abuse. Most people don’t recognise it as such, but they’re left feeling somewhat empty by it. It’s the most common factor in people with addictions.

Given this knowledge about where addiction comes from, why are most conventional treatments largely unsuccessful?

It’s a very difficult illness to treat, because of the availability of drugs and alcohol, the problem of social deprivation and poverty, homelessness and poor housing, racism, exclusion, poor education, lack of childcare, etc. If I had a magic wand and could instantly cure an addiction patient, but then sent them back to their dire home situation with transgenerational lack of hope, poverty and exclusion, they’re just going to pick up their addiction again. So it’s a very multidisciplinary problem with multiple factors that cause and maintain it, and we need to address all those factors.

Why then do psychedelics seem to do better in the treatment of addictions than conventional treatments?

Because underlying addiction, and many if not most chronic mental disorders, is rigidity. Stuck rigid mental narratives about self and the world, which arise early in life as a results of early experiences, in other words, the very core building blocks of our personality, which stay with us for life. The majority of mental health treatments, and certainly all the medicines we use, like SSRI’s, don’t do anything to those narratives, they just paper over the cracks and treat the overlying symptoms. In my experience, psychedelics are the best new form of pharmacology that we’ve come across that has the potential to actually tackle those narratives and allows people to build them up in a new, more positive way.

You’re currently conducting a study with MDMA to treat alcohol addiction. This is the first time MDMA is used for that indication. Why did you choose MDMA over psilocybin?

I was always interested in doing an MDMA study. Five years ago, I was in communication with MAPS about an MDMA/PTSD study. But then I got an offer from a rich benefactor which allowed me to do whatever I wanted. As I was working in addictions at the time, I decided to branch away from PTSD. I was acutely aware of alcoholism as being the number one addiction problem with a massive clinical and personal burden, and a very difficult one to treat. I also liked the fact that no-one else had ever suggested MDMA for addiction. Since trauma appears to be a big part of addictions, and MDMA has been shown to work in trauma treatment, it seemed to make sense that MDMA could work for addictions.

Do you think MDMA therapy and psilocybin therapy share the same paradigm?

They clearly have massive overlaps and similarities, for instance the fact of using a non-ordinary state of consciousness as an augmentation of psychotherapy. People would argue that MDMA isn’t a psychedelic, or at least not a classic one. However, I do think it fits into the same paradigm and I consider it a psychedelic psychotherapy tool. There are clearly also some big differences. With MDMA, you don’t get the ego dissolution that occurs on high doses of classic psychedelics. What you do get is a particular emphasis on empathy and connection with the positive, loving part of the self, and that’s why it’s good for trauma. The barrier to addressing trauma for many patients is this brick wall they hit, that prevents them from believing that they are worthy, after often spending decades believing they’re not. MDMA has this greater capacity than psilocybin to put you in a predominantly loving and warm state.

Where’s your MDMA/alcohol study at right now?

We have 14 participants, we finished dosing at the beginning of December, and we’re following everyone up to 9 months from the date of initial detox, so that will be until June. We’re assessing and analysing the data, and we’re writing the papers, which will be published in the first half of this year. This is a safety and tolerability study, with no placebo control group, which is what you have to do when using a new drug in a new condition for the first time. Obviously, we’re also looking at the subjects’ drinking behaviour and maintenance of abstinence and we’ll report on that, and the results look extremely promising. With conventional therapy, about 80% of patients go back to drinking in the next few months, and so far we have about 17% of people who went back to drinking again.

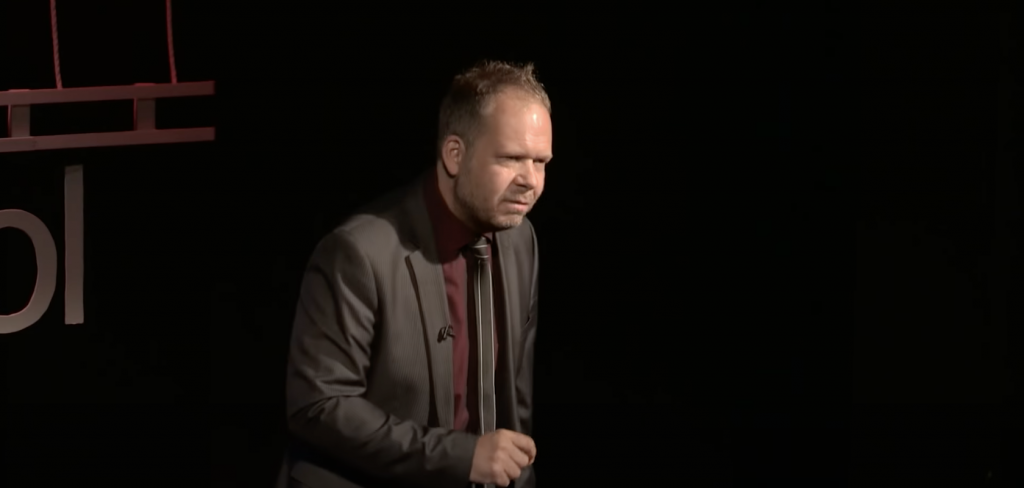

In his talk at ICPR 2020, Ben Sessa will elaborate on his MDMA/alcohol study and sketch future perspectives of psychedelic therapy research.