Psychedelic Assisted Therapy for Treating Addiction – Part 2

Psychedelic Assisted Therapy for Treating Addiction – Part 2

Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in the potential of psychedelic therapy as a novel approach for the treatment of addiction. This interest stems from a growing body of research exploring the therapeutic effects of psychedelic substances on addictive behaviors, particularly psilocybin and LSD. In his past seminar titled “Euphoria: The New Science of Addiction and Psychedelic Therapy,” Dr. Rayyan Zafar, a prominent researcher in the field, delves into the key insights and findings spanning from observational studies, clinical trials, and historical investigations with psychedelics in addiction treatment. Dr. Zafar sheds light on the historical context, scientific progress, and prospects of psychedelic therapy in addiction treatment. This blog post aims to summarize and analyze the key takeaways from Dr. Zafar’s seminar, providing readers with a deeper understanding of the evolving landscape of addiction treatment and the role of psychedelic therapy within it.

Key Takeaways from “Euphoria: The New Science of Addiction and Psychedelic Therapy”

Comprehensive Review of Psychedelic Therapy in Addiction Treatment

Dr. Zafar’s past seminar offered an in-depth examination of the potential of psychedelic therapy in treating addiction, drawing on a diverse range of research sources. The exploration begins with historical studies dating back to the mid to late 1900s, shedding light on the origins of psychedelic research and its developmental trajectory. Both classic (e.g. psilocybin, LSD, and DMT) and non-classical psychedelics (e.g. 6-MeO-DMT, ketamine, and MDMA) were discussed but due to the limited scope of this article, only the classic ones, psilocybin and LSD, will be highlighted.

The first realization of the powerful effect of LSD on mood and cognition in 1943 presumably marked the beginning of a modern era in which psychedelic drugs could be used to treat certain mental and behavioral conditions. From the 1940s and early 1970s, classic psychedelics were actively researched in humans as both a pharmacological tool to understand its effects on the mind and brain and as a therapeutics. Collectively, LSD was seen as a promising treatment for numerous serious mental health disorders such as depression, alcoholism, and other substance use disorders (Hofman, 1980). Furthermore, it has a favorable safety profile and had profound short-term psychological effects (Krebs). This led to a potential breakthrough in the treatment of various mental illnesses, including different forms of drug addiction (Belouin).

Between the late 1950s and early 1970s, approximately 40,000 patients worldwide suffering from various mental disorders, including substance use disorders, received treatment with psychedelics such as LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin, are documented over 1000 publications (Grinspoon). A key finding was that psychedelics are well-tolerated and induce a low risk of adverse side events (online event).

A controlled study investigating LSD’s efficacy in adjunction to psychotherapy in treating heroin addiction was influential. It was revealed that 33% of 36 participants in the treatment group (n= 73) maintained a abstinence after one year compared to the control group with a mere 5% success rate. However, only 5% maintain complete abstinence after the fulfilling the treatment program (Savage, 1973). Furthermore, a meta-analysis collected data about LSD in alcoholism from six randomized controlled trials that were published in the 1960s with over 500 participants and showed that LSD doubled the odds that patients would be abstinent at first follow-up, as defined by (OR = 2.07). Yet, this was not seen after a year (Krebs).

Even though there is quite a large amount of historical data showing a positive trend toward the therapeutic role of psychedelics in addiction treatment, the evidence from these studies remains inconclusive due to methodological inconsistencies. More specifically, these inconsistencies encompassed deficiencies in study design, such as the lack of proper controls, blinding, follow-up protocols, statistical analyses, and the utilization of validated assessments, as evaluated through contemporary research standards (Rucker).

Groundbreaking Investigations into Addiction Treatment with Psychedelic-assisted Therapy

The widespread use of psychedelics in the 1960s fueled a counterculture movement, prompting a political backlash and leading to increased regulatory controls by the FDA. This culminated in the establishment of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) in 1970 under Richard Nixon, effectively halting psychedelic research (Belouin). However, efforts to explore the therapeutic potential of psychedelics resumed in the 1990s with renewed scientific interest and advanced research methodologies (Belouin; Zafar).

Dr. Zafar provided an overview of the latest findings from these investigations, illuminating the favorable prospects of psychedelics in addiction recovery. Ongoing clinical trials exploring the potential therapeutic role of psychedelics in addiction cover a diverse spectrum of substances and addiction types, ranging from alcohol and tobacco to methamphetamine and gambling addiction. Due to the limited scope of this article, only psilocybin in alcohol and tobacco will be highlighted. These trials aim to expand upon initial findings and set the stage for larger-scale studies that would ultimately secure regulatory approval.

The promising results of earlier research on psychedelics and alcohol addiction have prompted a modern replication open-label study examining psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence (Bogenschutz et el., 2015). In the little sneak preview of last week, the study of psilocybin in conjunction with Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) was discussed. The figure illustrates the change in percent drinking days and percent heavy drinking days. The blue line in the graph represent the % of drinking days while the red line represent the % heavy drinking days. After the first administration with psilocybin, both percent drinking and heavy drinking days were statistically significant lower than baseline in all the follow-up points.

To explore the relationship between the intensity of the psilocybin-induced experience with changes in drinking behavior, the acute effects of psilocybin were measured by the Mystical Experiences Questionnaire (MEQ). It was also found to correlate with changes in drinking behavior, craving, and self-efficacy (Bogenschutz, 2015).

The mystical experiences induced by psilocybin are characterized by immediate sensations of unity, sacredness, a sense of understanding beyond ordinary knowledge, positive mood, transcendence of notions of space and time, and an inability to adequately describe the experience (e.g., ineffability; Griffiths, 2006). These dimensions seem to be common across ages, cultures, ethnicities, and genders (online seminar Johnson). The hallmark of the mystical experience lies in the profound sense of being influenced by forces greater than oneself, often accompanied by intense emotions, sparking enduring and transformative changes in one’s life (Miller).

To build upon the findings of the study of Bogenschutz et al. (2015), the research group investigated psilocybin in a so-called phase 2 double-blind randomized clinical trial (Bogenschutz, 2022). On one hand, it was observed that the psilocybin group had lower percentage in heavy drinking days and mean daily alcohol consumption (number of standard drinks per day) compared to the group that was given diphenhydramine as a control. On the other hand, the percentage of drinking days was not statistically reduced (29 in psilocybin group vs 43 in control groups). However, important limitations need to be pointed out. There were some methodological issues that could lead to a higher risk of making incorrect inferences about the data.This study is currently undergoing replication in larger phase III trials across multiple centers, advancing toward creating more data regarding the efficacy of the psychedelic drug and potential marketing authorization for this indication (Zafar).

The effects of psilocybin have also been investigated in conjunction with CBT for the treatment of tobacco addiction. In this open-label study, individuals were given two to three moderate to high doses (20 and 30 mg/70kg) of psilocybin (Johnson, 2017). Results based on urinary and breath analyses showed that 60% of the group did not smoke after one year of follow-up. This is a seemingly big difference compared to the 35% of what is usually observed in traditional tobacco treatment paradigms (Cahill, 2014). In the acknowledgment of the lack of drawing definitive conclusions based on open-label studies and the lack of a control group, a randomized comparative efficacy study has been performed and the results remain yet to be published.

Future Applications with Neuroimaging Techniques

Various neuroimaging techniques are able to provide insights into the neurobiological mechanisms of psychedelic therapy and how these relate to clinical outcomes in the treatment of addiction. These techniques include functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scans and enable researchers to map changes in both brain activity and connectivity, offering a deeper understanding of addiction mechanisms and treatment outcomes. Despite the relative scarcity of literature on the neurobiological mechanisms of psychedelics in addiction, recent studies have shed light on potential pathways such as reward, inhibitory control, and stress (Hayes).

Neuroimaging studies are invaluable in identifying biomarkers associated with substance dependence. These biomarkers serve as an objective measurement of bodily activity and, thus, aim to elucidate the mechanisms and conditions under which treatments prove effective. For instance, PET and SPECT, have enabled researchers to delve into the molecular dynamics of addiction within the living human brain. These methods have unveiled specific neuroreceptor biomarkers associated with different subclasses of addiction. Take, for example, the findings regarding dopamine receptors in alcohol and stimulant use disorder (Nutt et al., 2015), opioid receptors in cocaine (Gorelick et al., 2005), and opioid dependence (Williams et al., 2007). Such insights have not only paved the way for a deeper understanding of addiction pathology but also presented novel targets for therapeutic intervention.

Furthermore, by utilizing radioligands, neurotransmitter release studies have offered valuable insights into the dynamics of neurotransmission in addiction. The dopamine system has been widely implicated in addiction theory (Nutt, 2015; Zafar). In addiction, specifically, a blunted dopamine release in a brain region called the nucleus accumbens has been observed after a drug was given. When investigating the effect of psychedelics on addiction, it has been suggested that there is a potential link between psychedelics and dopamine release (Martin et al., 2024; Vollenweider et al. 1999). Yet, so far neurochemical studies have been done in non-humans and futher research is warranted (Nutt, 2015).

Dr. Zafar discusses that advanced multimodal neuroimaging techniques are necessary to directly assess the effects of psychedelic therapy on neurotransmission and brain function in individuals with addiction. For example, multimodal imaging studies combining PET and fMRI have proposed that psychedelic therapy may lead to increases in endogenous dopamine levels in addiction disorders, potentially reflecting improved brain function and treatment outcomes. One of his future scientific endeavors will investigate using fMRI and EEG to investigate differences between pre-and post-administration with psilocybin. Ultimately, these advances ultimately pave the way for more personalized and efficient approaches to address substance dependence (Moeller).

Addressing Challenges and Knowledge Gaps

While the collective data on psychedelics and addiction suggests a positive trend toward reducing substance use, and cravings, and fostering abstinence compared to conventional treatments, several critical knowledge gaps and controversies persist, necessitating further exploration and clarification. Besides the limitations associated with naturalistic, observational, open-label, and animal studies, we will highlight some knowledge gaps that are critical to address when exploring psychedelics and addiction. Indeed, when one door closes, another hundred seem to open.

One of the main remaining questions is: “What mediates the long-term effects of psychedelics?”.

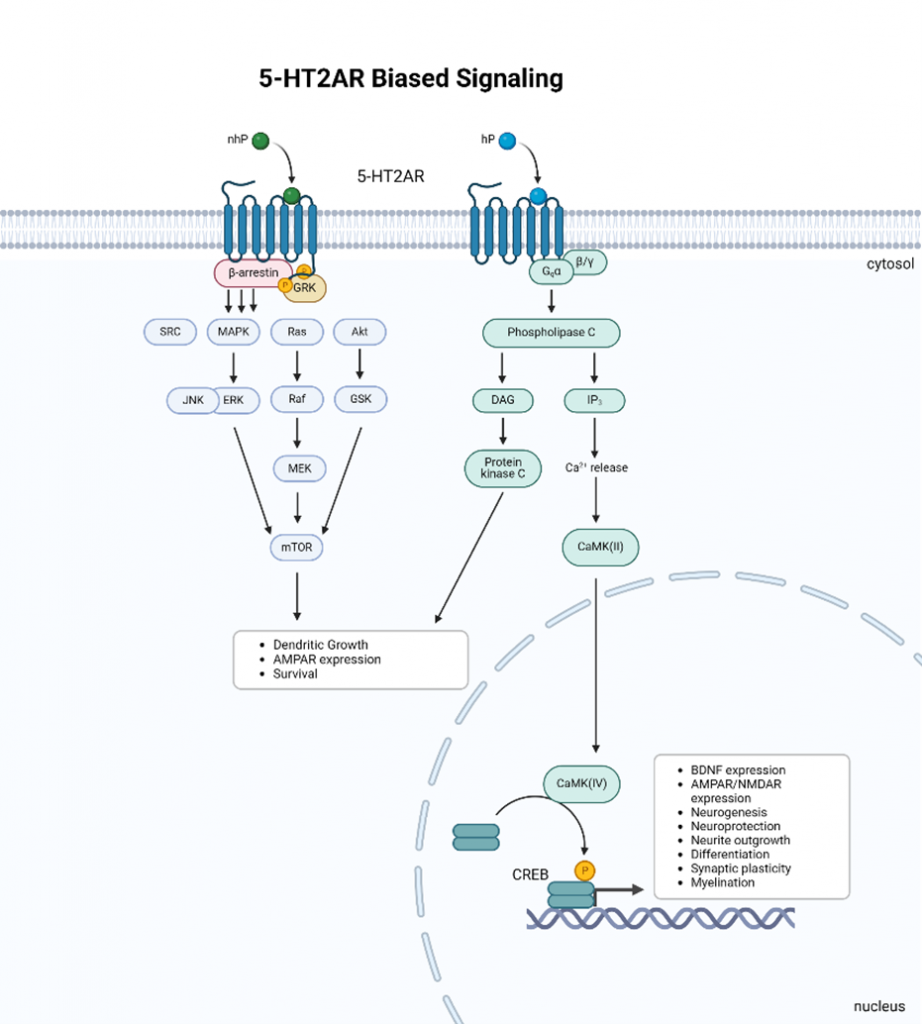

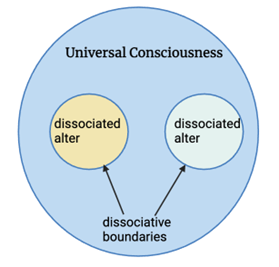

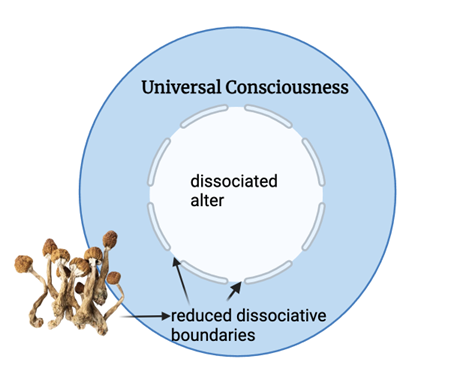

The enduring psychological and behavioral changes observed after psychedelic use may be partly influenced by the immediate, often subjectively positive effects of 5-HT2A receptor agonists, which are occasionally described as mystical or transcendent (Bogenschutz 2015; Calder; Griffiths 2006, 2008, 2011; Johnson 2017; Rothberg; Tap; Yaden). Griffiths (2011) even found that psilocybin can affect the Big Five personality traits, typically considered stable, by increasing openness. Similar associations between greater mystical experiences and improved outcomes were observed in psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) for smoking cessation (Johnson, 2017). The findings suggest that psilocybin-assisted treatment has lasting impacts beyond the drug’s immediate effects, with participants ranking their psilocybin experiences as some of the most personally significant and spiritually impactful, correlating with higher smoking cessation rates (Johnson 2017).

While these studies did not explicitly focus on spirituality, the findings raise questions about its role in the effects of psychedelic drugs on addiction. The emotion of awe is suggested as a crucial mechanism driving mystical experiences during psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (Kan). Awe fosters feelings of interconnectedness and unity, which are central to the transformative effects of psychedelic therapy (Griffiths, 2008). Data indicates that more profound mystical experiences increase the likelihood of smoking cessation (Johnson, 2017). However, not all mystical experiences lead to lasting change, and individuals may return to their previous state. Future randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials with multiple follow-up assessments are necessary to establish causality and determine the clinical significance of these mechanisms.

Another remaining question concerns the use of a particular therapeutic framework when psychedelics are administered to individuals with addiction. The literature is clear that psychotherapy plays a crucial role in addiction treatment, but it remains unknown what the right amount and particular type of psychotherapeutic intervention and relapse prevention is best. Some studies indicate that group therapy alongside psychedelic use may enhance group connectedness and interpersonal understanding, potentially promoting prosocial behavior (Ponomarenko). While mystical experiences often foster profound connections with others and the universe, solo settings remain prevalent, though both solo and group therapies have shown no significant differences in mental health perceptions (Byrne).

Another remaining question is “How do psychedelics impact the neural circuits implicated in addiction?” Answers to these questions can give insights into how to optimize the development of psychedelic-assisted therapies. Psychedelics may disrupt networks associated with addiction and enhance connectivity across the brain, fostering neuroplasticity and facilitating the relearning of behaviors (Carhart-Harris; Calder; Nutt 2023; online event; Tap). However, understanding these neuroplasticity mechanisms remains limited, with studies primarily conducted on animal models and cell lines (Calder)

Become a member if you would like to know the details of the past online seminar about psychedelics and addiction!

Conclusion

In conclusion, the field of addiction treatment is undergoing a profound transformation with the exploration of psychedelic therapy. Early research indicates that psychedelics like psilocybin and LSD show a positive trend in reducing addictive behaviors, supported by both historical and somewhat by modern clinical trials. By leveraging cutting-edge techniques, neuroimaging studies, researchers can elucidate the underlying mechanisms of psychedelic interventions and tailor treatments to individual needs. Despite the promising data, methodological inconsistencies and knowledge gaps remain, necessitating further rigorous research. Looking ahead, the future of psychedelics and addiction holds some promise, fueled by groundbreaking research, innovative treatment modalities, and a growing understanding of the complex interplay between neuroscience, psychology, and pharmacology.

By Gwendolyn Drossaert

Become a member to get access to recordings of past and upcoming live online events with leading experts in psychedelic research and therapy.

References

- Belouin, S. J., & Henningfield, J. E. (2018). Psychedelics: Where we are now, why we got here, what we must do. Neuropharmacology, 142, 7-19.

- Bogenschutz, M. P., Forcehimes, A. A., Pommy, J. A., Wilcox, C. E., Barbosa, P. C., & Strassman, R. J. (2015). Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. Journal of psychopharmacology, 29(3), 289-299.

- Bogenschutz, M. P., Ross, S., Bhatt, S., Baron, T., Forcehimes, A. A., Laska, E., … & Worth, L. (2022). Percentage of heavy drinking days following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy vs placebo in the treatment of adult patients with alcohol use disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry, 79(10), 953-962.

- Byrne, K. J., Lindsay, S., Baker, N., Schmutz, C., & Lewis, B. (2023). In naturalistic psychedelic use, group use is common and acceptable. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 7(2), 100-113.

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Nutt, D. J. (2017). Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors. Journal of psychopharmacology, 31(9), 1091-1120.

- Cahill, K., Stevens, S., & Lancaster, T. (2014). Pharmacological treatments for smoking cessation. Jama, 311(2), 193-194.

- Calder, A. E., & Hasler, G. (2023). Towards an understanding of psychedelic-induced neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 48(1), 104-112.

- Cameron, L. P., Tombari, R. J., Lu, J., Pell, A. J., Hurley, Z. Q., Ehinger, Y., … & Olson, D. E. (2021). A non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogue with therapeutic potential. Nature, 589(7842), 474-479.

- Griffiths, R. R., Johnson, M. W., Richards, W. A., Richards, B. D., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. (2011). Psilocybin occasioned mystical-type experiences: immediate and persisting dose-related effects. Psychopharmacology, 218, 649-665.

- Griffiths, R. R., Richards, W. A., Johnson, M. W., McCann, U. D., & Jesse, R. (2008). Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later. Journal of psychopharmacology, 22(6), 621-632.

- Griffiths, R. R., Richards, W. A., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. (2006). Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology, 187, 268-283.

- Grinspoon, L., & Bakalar, J. B. (1979). Psychedelic drugs reconsidered (Vol. 168, pp. 163-166). New York: Basic Books.

- Hayes, A., Herlinger, K., Paterson, L., & Lingford-Hughes, A. (2020). The neurobiology of substance use and addiction: evidence from neuroimaging and relevance to treatment. BJPsych Advances, 26(6), 367-378.

- Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2017). Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 43(1), 55-60.

- Gorelick, D. A., Kim, Y. K., Bencherif, B., Boyd, S. J., Nelson, R., Copersino, M., … & Frost, J. J. (2005). Imaging brain mu-opioid receptors in abstinent cocaine users: time course and relation to cocaine craving. Biological psychiatry, 57(12), 1573-1582.

- Krebs, T. S., & Johansen, P. Ø. (2012). Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 26(7), 994-1002.

- Lingford-Hughes, A., Reid, A. G., Myers, J., Feeney, A., Hammers, A., Taylor, L. G., … & Nutt, D. J. (2012). A [11C] Ro15 4513 PET study suggests that alcohol dependence in man is associated with reduced α5 benzodiazepine receptors in limbic regions. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 26(2), 273-281.

- Martin, D. A., Delgado, A., & Calu, D. J. (2024). The psychedelic, DOI, increases dopamine release in nucleus accumbens to predictable rewards and reward cues. bioRxiv, 2024-03.

- Miller, W. R., & C’de Baca, J. (2001). Quantum change: When epiphanies and sudden insights transform ordinary lives. Guilford Press.

- Moeller, S. J., & Paulus, M. P. (2018). Toward biomarkers of the addicted human brain: Using neuroimaging to predict relapse and sustained abstinence in substance use disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 80, 143-154.

- Nutt, D. J., Lingford-Hughes, A., Erritzoe, D., & Stokes, P. R. (2015). The dopamine theory of addiction: 40 years of highs and lows. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(5), 305-312.

- Nutt, D., Spriggs, M., & Erritzoe, D. (2023). Psychedelics therapeutics: what we know, what we think, and what we need to research. Neuropharmacology, 223, 109257.

- Ponomarenko, P., Seragnoli, F., Calder, A., Oehen, P., & Hasler, G. (2023). Can psychedelics enhance group psychotherapy? A discussion on the therapeutic factors. Journal of psychopharmacology, 37(7), 660-678.

- Rothberg, R. L., Azhari, N., Haug, N. A., & Dakwar, E. (2021). Mystical-type experiences occasioned by ketamine mediate its impact on at-risk drinking: Results from a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 35(2), 150-158.

- Rucker, J. J., Iliff, J., & Nutt, D. J. (2018). Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology, 142, 200-218.

- Savage, C., & McCabe, O. L. (1973). Residential psychedelic (LSD) therapy for the narcotic addict: a controlled study. Archives of general psychiatry, 28(6), 808-814.

- Stokes, P. R., Benecke, A., Myers, J., Erritzoe, D., Watson, B. J., Kalk, N., … & Lingford-Hughes, A. R. (2013). History of cigarette smoking is associated with higher limbic GABAA receptor availability. Neuroimage, 69, 70-77.

- Vollenweider, F. X., Vontobel, P., Hell, D., & Leenders, K. L. (1999). 5-HT modulation of dopamine release in basal ganglia in psilocybin-induced psychosis in man—a PET study with [11C] raclopride. Neuropsychopharmacology, 20(5), 424-433.

- Yaden, D. B., Berghella, A. P., Regier, P. S., Garcia-Romeu, A., Johnson, M. W., & Hendricks, P. S. (2021). Classic psychedelics in the treatment of substance use disorder: potential synergies with twelve-step programs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 98, 103380.

- Williams, T. M., Daglish, M. R., Lingford-Hughes, A., Taylor, L. G., Hammers, A., Brooks, D. J., … & Nutt, D. J. (2007). Brain opioid receptor binding in early abstinence from opioid dependence: positron emission tomography study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(1), 63-69.

- Online event

- Tap, S. C. (2024). The potential of 5‐methoxy‐N, N‐dimethyltryptamine in the treatment of alcohol use disorder: A first look at therapeutic mechanisms of action. Addiction Biology, 29(4), e13386.

- Zafar, R., Siegel, M., Harding, R., Barba, T., Agnorelli, C., Suseelan, S., … & Erritzoe, D. (2023). Psychedelic therapy in the treatment of addiction: the past, present and future. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1183740.