Feature image by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash

“Life is the extrinsic appearance of a dissociative process in a universal consciousness.”

-Bernardo Kastrup

Meet Bernardo Kastrup

Are you ready to flip the script of reality and dive deep into a world that is purely mental and not so much physical? Meet the founder of Essentia Foundation , PhD. Bernardo Kastrup. Blending neuroscience and philosophy, his captivating ideas are embedded in the concept of analytical idealism. Brace yourself for a mind-bending journey beyond the confines of conventional thought. Bernardo Kastrup lectured and joined the conversation at an online community event at OPEN Foundation. Discover upcoming events here. At the bottom of this post, you can find an in-depth interview with Bernardo Kastrup, OPEN Foundation and Drug Reporter.

The next lines aim to give you a general understanding of his ideas about the reality of the mind and eventually bridge analytical idealism with psychedelic experiences.

Does our perception align with reality?

Let’s start by taking your eyes away from the screen and observing what you perceive in the world around you. The wall in your room, the trees in the park, the clouds in the sky or the sounds of the birds. Intuitively, we believe that what we perceive accurately reflects the world outside of us – a mirrored image of the external world in our consciousness.

If this were true – we would have a fully transparent window into the world outside – we would all drown in what the analytical idealist Bernardo Kastrup calls “an entropic soup”. To understand that metaphor it is important to grasp the general concept of entropy.

What is Entropy?

Entropy is a fundamental concept in thermodynamics that is often described as the measure of randomness or disorder of a system. Imagine a brand new deck of cards that has never been shuffled. This represents low entropy because there is not a lot of randomness. Now think about shuffling this deck of cards. We created a high entropic state that is not very organized but rather chaotic. Let us keep this concept in mind when we dive deeper into the concept of analytical idealism.

“The entropic soup”: the world looks nothing like what we perceive

From the perspective of “the entropic soup”, the world around us is highly entropic because it’s full of complexity, randomness, and disorder. Think about all the diverse and chaotic phenomena we encounter every day: from the unpredictable weather patterns to the bustling traffic on city streets, to the entangled interactions of living organisms in highly complex ecosystems. According to the second law of thermodynamics, if we perceive the world as it is, including the immense chaos and disorder, our brains would all drown in a hot, entropic soup. Consequently, through evolution, our brains learn to make sense of the world by using a simplified “user interface” or a “dashboard” that can help us navigate and make sense of a highly chaotic environment. Like a dashboard in a pilot’s cockpit that depicts the wind strength by representing it on a dial with an arrow (see picture below). The dial does not show the wind itself but is rather a representation of the wind. Bernardo states that “the world in itself looks nothing like what we perceive. We are merely using a virtual user interface to make sense of the chaos outside. More about that later. First, we will investigate mainstream ideas of consciousness and the world.

Pilot making sense of the world with the help of a dashboard.

Foto by William Topa, unsplash

The limitation of physicalism: The hard problem of consciousness

According to physicalism, all there is can be described in quantities. Physical relations and matter are the basis of everything. Therefore, the reality of the mind and the world itself – in the eyes of a physicalist – can be fully explained by abstract quantitative mathematical relationships. Hence, the mind including all of its rich qualities, such as the experience of rain on your skin or the smell of freshly baked cookies, is caused by physical brain activity.

However, Bernado Kastup does not agree with this view and states “There is something very wrong with this story that brain activity generates conscious experience.” Indeed, cognitive neuroscientists have still not solved the “hard problem of consciousness” (as defined by David Chalmers). The question remains how can a purely quantitative, physical entity give rise to complex qualitative experiences?

Bernardo suggests we imagine a scenario where a scientist has all the knowledge about the brain’s structure, its neurons, and how they interact. They know everything about brain activity when a person sees the colour red – the firing of neurons, the release of chemicals, and so on. However, no matter how much they understand about the brain’s physical processes, they still can’t explain why seeing the color red feels the way it does to the person experiencing it. This inability to explain subjective experience purely in terms of physical processes is what constitutes the hard problem of consciousness.

Perhaps it is necessary to shift our world paradigm to allow answers to this problem. One proposed solution may be Bernardo Kastrup’s analytical idealism.

What is analytical idealism?

Contrary to physicalism, in the philosophical perspective of idealism, reality is fundamentally mental or dependent on consciousness. In other words, the external world and its phenomena are products of mental constructs or perceptions. Similarly, analytical idealism is embedded in idealism and posits that the essence of the universe is an “intrinsic view”, suggesting that reality fundamentally resides in subjective experience. Analytical Idealism is rooted in and driven by post-enlightenment principles such as conceptual parsimony, coherence, internal logical coherence, explanatory capability, and empirical sufficiency.

How does analytical idealism explain consciousness and reality?

While physicalism states that brain activity causes experience, analytical idealism argues that brain activity is just the depiction of experience. To understand Kastrup’s argument, one needs to take a few steps back and briefly review the basic assumptions that analytical idealism is based on.

Kastrup emphasizes that there are three empirical givens that we can be fully certain about:

1) There is experience.

Before we start to theorize, all we have is experience.

2) Brain function is a perceptual experience

For example, a neurologist who perceives the image created with a brain scanner.

3) The brain is made of what we colloquially call and perceive as “matter”.

Importantly, whatever we call matter, whatever it is, it underlies both the brain and the universe and thus creates space for a kinship between them.

Building on these statements, analytical idealism states that brain function is what one’s inner conscious life looks like when it is observed by a neuroscientist through a brain scanner. Consequently, Bernardo Kastrup emphasizes that brain function does not generate a conscious inner life, because this leads to the “hard problem of consciousness”. Rather, he elaborates that conscious inner life is intrinsic; it is the essence that can be observed from an outside perspective with the help of a brain scanner. In other words, a brain scan is merely the representation of conscious inner life, but it is not consciousness itself.

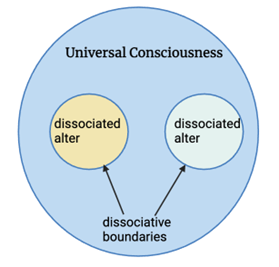

The universal consciousness with multiple personalities

Bernardo Kastrup’s analytical idealism conceptualizes and builds upon one universal consciousness. To introduce this idea, the philosopher often uses the analogy of Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). DID is a psychiatric condition that involves the presence of two or more distinct personality states (also known as “alters”) within the same individual. Using this analogy, he argues that we are dissociated alters of universal consciousness. Because of dissociation, we believe to be individual minds. With that being stated, all that lies beyond our dissociative boundary constitutes a broader “universal consciousness” and thus is mental by itself.

How do we make sense of the world according to analytical idealism?

One important concept in the theory of analytical idealism is “impingement”. Imagine you had a stressful fight with your housemate, partner or friend just before work. During work, you have to function, which is why your mind automatically compartmentalizes the stressful event and “parks it” to set it aside. According to Kastrup, this is a kind of “deliberate light dissociation. Your mind as a whole did not stop to feel the emotions, they are just more in the background, dissociated from your executive ego. However, you notice that you are easily irritable or disorganized during your work. The stressful event can still influence the ego despite the creation of a dissociative boundary. In other words, the mind outside of the boundary impinges across the dissociative boundary on the ego within.

What happens outside of our dissociative boundary are ideas and emotions that impinge on our mental dissociative boundary and result in us perceiving the world outside. Kastrup explains that the dissociative boundary “forms a screen on which outside mentation impinges, or is projected as perceptions”.

The dashboard in the pilot’s cockpit is the extrinsic appearance of the world outside as represented by dials measuring wind, temperature, etc. Similarly, the “perception is the extrinsic appearance, as represented in an alter`s dashboard of dials, of the ideas and emotions in universal consciousness”.

Model displaying how we are all dissociated alters with dissociative boundaries of a larger, shared universal consciousness.

Created with biorender.

How do neural correlates of psychedelics substantiate the argument of analytical idealism?

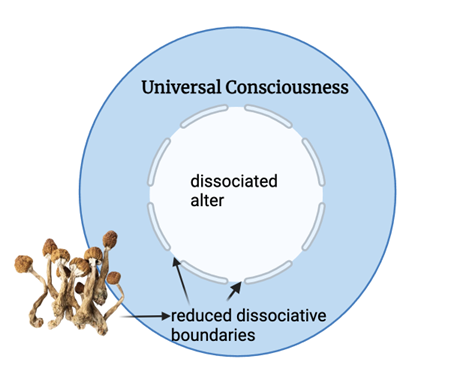

Psychedelic experiences are often perceived as one of the most profound experiences of a user’s life. People often report that psychedelics induce a rich altered state of consciousness with enhanced senses and deep insights. Interestingly, the intense psychedelic experience does not correlate with increased brain activity, but neuroscientists show that rather the opposite holds! Psychedelics reduce overall brain activity. Especially, from the perspective of physicalism this is surprising. The argument of physicalism assumes that brain activation is the cause of subjective experience, so how is it possible that lower brain activity can give space for an enriched experience?

Psychedelics reduce dissociation and increase entropy

Kastrup explains that the reduced brain activity, induced by psychedelic substances, represents reduced dissociation. In other words, brain activity measured by brain scans is a picture of this dissociation process. Psychedelics reduce dissociation which correlates with a richer, more intense and profound experience due to the alleviation of dissociation itself. By reduction of dissociation, the dissociative boundary becomes more permeable, which allows the transpassing of elements from beyond the boundary to reach the alter within. We experience trance, the trespassing of mental elements across dissociative boundaries, while our brain activity is largely reduced.

Model displaying that psychedelics (here psilocybin-containing mushrooms) can make the dissociative boundary more permeable.

Perhaps, as Kastrup suggests, the increased connection to the world outside and other people, as perceived during a psychedelic experience may reflect the reduction of dissociation, which brings us closer to “universal consciousness” and the other alters by allowing the crossing of mental entities from beyond the boundary that surrounds our alter.

Bernardo argues that the end of life is the end of the dissociative process. By reducing dissociation we may get into a similar state like death. If psychedelics reduce dissociation, this should elicit an experience similar to death. Indeed, psychedelics can induce the experience of “ego death” (dissolution of the sense of self) and have been found to share similarities with near-death experiences, which is consistent with Kastrups theory. This observation may further substantiate this theory.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Bernardo Kastrup’s analytical idealism presents a thought-provoking perspective on the nature of reality and consciousness. By challenging the traditional paradigms of physicalism (and others), Kastrup offers a framework where consciousness is not merely an emergent property of brain activity but is fundamental to the fabric of existence. Through concepts like dissociation and impingement, he elucidates how our perception of the world is shaped by our mental processes, bridging neuroscience with philosophy. Furthermore, Kastrup’s exploration of psychedelic experiences provides intriguing insights into the relationship between consciousness, brain function, and the dissolution of ego boundaries. Overall, Kastrup’s ideas invite us to reconsider our understanding of reality, consciousness, and the interconnectedness of the universe in a manner that transcends conventional thought.

Previous online event hosted by OPEN Foundation. See upcoming events here. Subscribe to our newsletter to get updated on events.

Interview with Bernardo Kastrup, PhD at ICPR 2022, hosted by OPEN Foundation.