This is Part I of a dual feature on the current state of research and development of non-hallucinogenic psychedelics. In this installment, we introduce the rationale and history behind this emerging field and highlight the major efforts underway across different pharmacological classes. Part II examines the limitations of the techniques, the challenges of psychedelic translatability, and the medical and clinical models these compounds might follow.

You can read Part II of the series here.

A Field Split on the Role of Subjective Experience

As of 2025, our field is still debating whether the profound subjective experiences triggered by psychedelics are required for their therapeutic benefit. A memorable moment in this discussion came in 2020, when Yaden & Griffiths (2020) and David Olson (2020) published back-to-back papers, each championing one side of the dilemma.

Focusing on clinical trials and correlational analyses showing that higher ratings of mystical experience predict greater symptom reduction, Yaden & Griffiths contended that the subjective effects are necessary for the enduring benefits of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapies, arguing that cathartic states, mystical-type experiences, and other types of altered states of consciousness are key mediators of the emotional breakthroughs that foster long-term improvements of psychedelic-assisted therapies. On the other side, discussing preclinical and early clinical data, Olson countered that, upon binding to different brain receptors, psychedelics trigger a series of molecular, neuronal, and brain network-level events that, independently of an acute conscious experience, produce those persistent cognitive and behavioral changes, suggesting a possible dissociation of subjective phenomenology from therapeutic mechanisms, and therefore the plausibility of “non-hallucinogenic psychedelics”.

What counts as a (non-)hallucinogenic psychedelic

The term psychedelic drug remains contested across pharmacology, neuroscience, and clinical and recreational practices. Nichols’ 2016 Pharmacological Reviews article describes that, in the late 1960s, these molecules were all lumped together in a class known first as psychotomimetics (suggesting that they foster psychosis) and then hallucinogens (again somewhat discrediting the class and suggesting that they principally produce hallucinations). According to Nichols, the most rigorous, useful, and widely adopted definition for psychedelics is “compounds that act as full or partial agonists at the serotonin 2A receptor (meaning they bind to the 5-HT2AR on the neuron and trigger a full or partial signaling cascade) and reliably produce profound alterations in perception, cognition, and self-experience”.

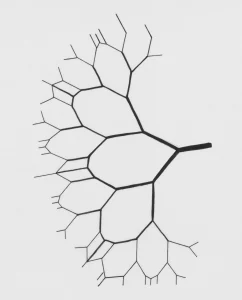

This 5-HT2AR-centric view anchors the “classic psychedelics” or tryptamines (DMT, Psilocybin), phenethylamines (mescaline), and lysergamides (LSD) under a coherent pharmacological umbrella: shared mechanism and outcome despite diverse chemical scaffolds. Within this framework, the notion of a non-hallucinogenic psychedelic emerges from work seeking to decouple 5-HT2AR–mediated therapeutic potential from its associated “trippy” subjective experience.

From Psychedelics to Psychoplastogens

Olson and colleagues (2018) proposed the term “psychoplastogen” to describe small molecules capable of promoting structural and functional neuroplasticity, independent of subjective phenomenology. This (if I may say, somewhat redundant) category includes all endogenous neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, and hormones, and classic/atypical psychedelics and newly engineered small molecules for their brain plasticity effects. Hence, in this framework, a non-hallucinogenic psychedelic is best understood as a molecule that binds to the 5-HT2AR and triggers the therapeutically beneficial neurobiological changes without inducing the characteristic subjective effects. Importantly, these drug-development programs operate under the assumption that this conceptual backbone will yield safer, more scalable, and accessible interventions, given an understanding that places hallucinations as undesirable side effects of both classic and atypical psychedelic drugs.

Atypical Psychedelics and Blurred Boundaries

It is important to mention that contemporary research routinely blurs these receptor-centric boundaries. Molecules such as ketamine, MDMA, or ibogaine are sometimes referred to as atypical psychedelics, a class of drugs that bind to different receptors and elicit overlapping subjective states and therapeutic outcomes, but produce distinct neurobiological signaling cascades and generally lack the canonical hallucinogenic signature characteristic of the classic psychedelics.

Nevertheless, these molecules are crucial to examine because (1) they broaden the discussion about which mechanisms are necessary or sufficient both for classic hallucinations and clinical efficacy, (2) because they have also undergone the probing of “molecular de-hallucination” and (3), because despite Nichol’s definition, researchers and users alike are still considering MDMA a psychedelic substance anyway.

The Current state of R&D on canonical non-hallucinogenic psychedelics

In the last five years, non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analog programs have progressed from proof-of-concept chemistry to several lead molecules now in advanced preclinical and early clinical pipelines, as candidates with therapeutic promise for mood disorders without hallucinogenic liability.

To begin with a more familiar example, the LSD analog 2-Bromo-LSD shows partial agonism at multiple receptors (including the 5-HT2AR), reverses stress-induced behavioral deficits, and promotes cortical neuroplasticity, all while failing to elicit the rodent head-twitch response (HTR).

This concept will be examined in more detail in our Part II. For now, it is essential to note that the HTR serves as a common proxy for evaluating a drug’s potential to induce 5-HT2AR-mediated psychedelic effects. Research has shown that the number of side-to-side head movements in rodents correlates in a dose-dependent manner with the intensity of hallucinogenic effects experienced by humans when using classic psychedelics.

At the forefront of the non-hallucinogenic psychedelics’ development efforts are:

- Delix Therapeutics, an American biotech company developing neuroplasticity-promoting therapeutics for central nervous system diseases

- The Olson Lab at UC Davis, whose studies exemplify how precision medicinal chemistry, combined with multimodal functional assays, could decouple 5-HT2AR-mediated molecular plasticity from the associated subjective effects.

One of their candidates is IBG, a conformationally restricted 5-MeO-DMT analog designed to retain therapeutic activity while lacking hallucinogenic signatures.

Structure–activity receptor pharmacology work showed that IBG has reduced potency at the 5-HT2AR and a markedly diminished HTR in mice as evidence of a non-hallucinogenic profile.

Zalsupindole, also produced and advanced by Delix using multiple behavioral paradigms such as social defeat and chronic stress to build a translational case, is an isotryptamine chemically optimized to enhance brain penetrance, dendritic spine density, and antidepressant-like effects comparable to ketamine and classic psychedelics while eliminating dissociative or hallucinogenic behaviors in rodents (meaning, no HTR).

Even more recently, Delix has produced isoindole-LSD derivatives (such as JRT) through purposely transposing atoms in the LSD scaffold, creating molecules that retain neuroplasticity while lowering hallucinogenic potential. Their strategies combine rational design, total synthesis, in vitro receptor-binding/functional synaptogenesis assays, and in vivo behavioral testing (HTR, depression-relevant tasks) to demonstrate therapeutic effects without causing hallucinations.

The efforts of this lab and company have produced DLX-159, a “next-generation psychoplastogen” that is already entering human trials, having shown robust 5-HT2AR-mediated rapid, enduring antidepressant-like effects and, of course, no HTR side effects.

Non-hallucinogenic oneirogens enter the pipeline

Sometimes labelled “dissociative psychedelics”, studying kappa-opioid receptor (KOR) agonists represents a parallel strategy to engineer another class of non-hallucinogenic atypical psychedelics, particularly from the iboga alkaloid family.

Ibogaine and its active metabolite, noribogaine, display complex, polypharmacological profiles that involve KOR activity but also include modulation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR), serotonin reuptake inhibition, and sigma-1 receptor interactions. Despite promising clinical and observational data regarding their therapeutic potential for the treatment of diverse mood and substance use disorders, their research has long been tempered by cardiotoxicity and intense oneirogenic or dissociatively-hallucinogenic experiences.

For the intrepid reader, avid for more information: the review by Iyer, Favela, Zhang, and Olson (2021) maps, in a very comprehensive way, the chemistry, receptor pharmacology, and biosynthetic logic of iboga alkaloids and provides the foundation for the rational design of safer, non-hallucinogenic engineered “ibogalogs”. The medicinal chemistry efforts described in this work highlight scaffold simplification, removal of cardiotoxic motifs, and the generation of more drug-like molecules through synthetic redesign rather than minor atomic additions and substitutions.

Again, Olson Lab and Delix mediated, Tabernanthalog (TBG) has emerged as the leading example of this approach. Reported in the 2021 Nature paper by Cameron et al. paper, TBG is a structurally simplified iboga analogue designed to eliminate cardiotoxicity and reduce hallucinogenic liability while retaining neuroplastic activity. The design strategy replaced the rigid iboga polycyclic system with a water-soluble scaffold while preserving key pharmacophores needed for intracellular signaling.

At a mechanistic and functional level, TBG increases dendritic spine density and enhances cortical neural plasticity in vitro and in vivo and, in rodents, produces rapid antidepressant-like effects and reduces alcohol intake and heroin-seeking behavior in self-administration paradigms, assays modeling depressive symptoms, and drug compulsive consumption and relapse vulnerability. Crucially, TBG does not induce the mouse HTR, leading the authors to classify it as non-hallucinogenic. Together, the iboga-derived analog program claims that oneirogenic scaffolds can be re-engineered toward safer, plasticity-promoting therapeutics. However, the precise mechanistic contributions of kappa-opioid signaling remain incompletely characterized.

Ketamine and the Search for Non-Dissociative Analogues

But what about ketamine? Why does nobody ever think about the next-generation non-hallucinogenic non-dissociative non-anesthetic arylcyclohexylamines?

Oh yes, you can bet people have been thinking about those, too. Unlike classic psychedelics, ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic that exerts its therapeutic and phenomenological, hallucinogenic-like effects via antagonism at the NMDAR (i.e., preventing its function), and engaging other systems such as the opioidergic, which seemingly critically mediates the antidepressant and anti-suicidal effects of ketamine.

As of 2026, there are no completely non-hallucinogenic structural analogues of ketamine; the closest option is its enantiomer, (R)-ketamine. However, this compound only slightly differs in its dissociative properties. Instead, the development of non-hallucinogenic “ketalogs” has primarily focused on functionally mimicking ketamine’s downstream mechanisms. This is achieved by modulating NMDAR and related circuits using different molecular scaffolds.

One example is Rapastinel, a positive allosteric modulator of the NMDAR developed by Allergan, a company known for creating and marketing a wide range of branded pharmaceuticals. Rather than blocking the receptor like ketamine, rapastinel enhances its activity, boosting long-term changes in brain prefrontal cortex function, and producing rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects in rodent forced swim tests, without causing hallucinations. However, despite promising preclinical data, rapastinel ultimately failed to meet its primary efficacy endpoint in Phase 3 trials as adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder. The same company developed Zelquistinel as a next-generation, significantly more potent NMDAR modulator that promotes activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex and produces rapid, sustained antidepressant-like effects in both the forced swim test and the chronic social-defeat rodent model, without causing hallucinations.

Accordingly, following the idea that selective enhancement of hippocampal excitability may be sufficient for rapid antidepressant responses, it has also been shown that downstream modulation of hippocampal circuitry can recapitulate ketamine-like antidepressant effects, independent of NMDAR activation and dissociative or psychotomimetic side effects. For instance, when L-655,708, a negative allosteric modulator of GABA-A receptors preferentially expressed in the hippocampus, was administered systemically to rats, it resulted in sustained antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test. Additionally, there was no HTR or self-administration liability, indicating a lack of abuse potential.

How Far We’ve Come, and What’s Next

Taken together, these programs illustrate how far the field has come in attempting to separate neuroplasticity from hallucinogenic experience. At the same time, they also point to many assumptions that still underlie this work.

In Part II, we will take a closer look at those assumptions, examining the limitations of current assays, the challenges of translatability of psychedelic and therapeutic effects, and the medical models and clinical realities that might shape the future of these compounds.

Stay tuned!

References

- The Subjective Effects of Psychedelics Are Necessary for Their Enduring Therapeutic Effects: Yaden DB, Griffiths RR. The Subjective Effects of Psychedelics Are Necessary for Their Enduring Therapeutic Effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020 Dec 10;4(2):568-572. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00194. PMID: 33861219; PMCID: PMC8033615.

- The Subjective Effects of Psychedelics May Not Be Necessary for Their Enduring Therapeutic Effects: Olson DE. The Subjective Effects of Psychedelics May Not Be Necessary for Their Enduring Therapeutic Effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020 Dec 10;4(2):563-567. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00192. PMID: 33861218; PMCID: PMC8033607.

- Psychedelics: Nichols DE. Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev. 2016 Apr;68(2):264-355. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011478. Erratum in: Pharmacol Rev. 2016 Apr;68(2):356. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.011478err. PMID: 26841800; PMCID: PMC4813425.

- Psychoplastogens: A Promising Class of Plasticity-Promoting Neurotherapeutics: Olson DE. Psychoplastogens: A Promising Class of Plasticity-Promoting Neurotherapeutics. J Exp Neurosci. 2018 Sep 19;12:1179069518800508. doi: 10.1177/1179069518800508. PMID: 30262987; PMCID: PMC6149016.

- A Non-Hallucinogenic LSD analog with Therapeutic Potential for Mood Disorders: Lewis V, Bonniwell EM, Lanham JK, Ghaffari A, Sheshbaradaran H, Cao AB, Calkins MM, Bautista-Carro MA, Arsenault E, Telfer A, Taghavi-Abkuh FF, Malcolm NJ, El Sayegh F, Abizaid A, Schmid Y, Morton K, Halberstadt AL, Aguilar-Valles A, McCorvy JD. A non-hallucinogenic LSD analog with therapeutic potential for mood disorders. Cell Rep. 2023 Mar 28;42(3):112203. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112203. Epub 2023 Mar 6. PMID: 36884348; PMCID: PMC10112881.

- A non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogue with therapeutic potential: Cameron LP, Tombari RJ, Lu J, Pell AJ, Hurley ZQ, Ehinger Y, Vargas MV, McCarroll MN, Taylor JC, Myers-Turnbull D, Liu T, Yaghoobi B, Laskowski LJ, Anderson EI, Zhang G, Viswanathan J, Brown BM, Tjia M, Dunlap LE, Rabow ZT, Fiehn O, Wulff H, McCorvy JD, Lein PJ, Kokel D, Ron D, Peters J, Zuo Y, Olson DE. A non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogue with therapeutic potential. Nature. 2021 Jan;589(7842):474-479. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-3008-z. Epub 2020 Dec 9. PMID: 33299186; PMCID: PMC7874389.

- Zalsupindole is a Nondissociative, Nonhallucinogenic Neuroplastogen with Therapeutic Effects Comparable to Ketamine and Psychedelics: Agrawal R, Gillie D, Mungenast A, Chytil M, Engel S, Wu MC, et al. (October 2025). “Zalsupindole is a Nondissociative, Nonhallucinogenic Neuroplastogen with Therapeutic Effects Comparable to Ketamine and Psychedelics”. ACS Chem Neurosci acschemneuro.5c00667.

- Molecular design of a therapeutic LSD analogue with reduced hallucinogenic potential: J.R. Tuck, L.E. Dunlap, Y.A. Khatib, C.J. Hatzipantelis, S. Weiser Novak, R.M. Rahn, A.R. Davis, A. Mosswood, A.M.M. Vernier, E.M. Fenton, I.K. Aarrestad, R.J. Tombari, S.J. Carter, Z. Deane, Y. Wang, A. Sheridan, M.A. Gonzalez, A.A. Avanes, N.A. Powell, M. Chytil, S. Engel, J.C. Fettinger, A.R. Jenkins, W.A. Carlezon, A.S. Nord, B.D. Kangas, K. Rasmussen, C. Liston, U. Manor, & D.E. Olson, Molecular design of a therapeutic LSD analogue with reduced hallucinogenic potential, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 122 (16) e2416106122, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2416106122 (2025).

- DLX-159: A Novel, Next Generation, Non-Hallucinogenic Neuroplastogen With the Potential for Treating Neuropsychiatric Diseases: Rasmussen K, Agrawal R, Felts A, Leach P, Gillie D, Mungenast A, et al. (2024). “ACNP 63rd Annual Meeting: Poster Abstracts P1-P304: P252. DLX-159: A Novel, Next Generation, Non-Hallucinogenic Neuroplastogen With the Potential for Treating Neuropsychiatric Diseases” (PDF). Neuropsychopharmacology. 49 (S1): 65–235 (207–207). doi:10.1038/s41386-024-02011-0

- The iboga enigma: the chemistry and neuropharmacology of iboga alkaloids and related analogs: Iyer RN, Favela D, Zhang G, Olson DE. The iboga enigma: the chemistry and neuropharmacology of iboga alkaloids and related analogs. Nat Prod Rep. 2021 Mar 4;38(2):307-329. doi: 10.1039/d0np00033g. PMID: 32794540; PMCID: PMC7882011.

- Attenuation of antidepressant and antisuicidal effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism: Williams NR, Heifets BD, Bentzley BS, Blasey C, Sudheimer KD, Hawkins J, Lyons DM, Schatzberg AF. Attenuation of antidepressant and antisuicidal effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Mol Psychiatry. 2019 Dec;24(12):1779-1786. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0503-4. Epub 2019 Aug 29. PMID: 31467392.

- Rapastinel mechanism (NMDAR PAM): Moskal JR, Burch R, Burgdorf J, et al. GLYX-13, an NMDA receptor glycine-site functional partial agonist, induces antidepressant-like effects without ketamine-like side effects. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2014. (PMID: 30544218)

- GLYX-13, a NMDA Receptor Glycine-Site Functional Partial Agonist, Induces Antidepressant-Like Effects Without Ketamine-Like Side Effects: Burgdorf J, Zhang XL, Nicholson KL, Balster RL, Leander JD, Stanton PK, Gross AL, Kroes RA, Moskal JR. GLYX-13, a NMDA receptor glycine-site functional partial agonist, induces antidepressant-like effects without ketamine-like side effects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 Apr;38(5):729-42. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.246. Epub 2012 Dec 5. PMID: 23303054; PMCID: PMC3671991.

- Allergan Announces Phase 3 Results for Rapastinel as an Adjunctive Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). PR Newswire, 2019.

- Zelquistinel Is an Orally Bioavailable Novel NMDA Receptor Allosteric Modulator That Exhibits Rapid and Sustained Antidepressant-Like Effects: Burgdorf JS, Zhang XL, Stanton PK, Moskal JR, Donello JE. Zelquistinel Is an Orally Bioavailable Novel NMDA Receptor Allosteric Modulator That Exhibits Rapid and Sustained Antidepressant-Like Effects. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022 Dec 12;25(12):979-991. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyac043. PMID: 35882204; PMCID: PMC9743962.

- Selective Pharmacological Augmentation of Hippocampal Activity Produces a Sustained Antidepressant-Like Response without Abuse-Related or Psychotomimetic Effects: Carreno FR, Collins GT, Frazer A, Lodge DJ. Selective Pharmacological Augmentation of Hippocampal Activity Produces a Sustained Antidepressant-Like Response without Abuse-Related or Psychotomimetic Effects. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017 Jun 1;20(6):504-509. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyx003. PMID: 28339593; PMCID: PMC5458335.

AUTHOR

MSc in Fundamental Neuroscience, PhD candidate in Psychedelic Neuropharmacology

Sergio is a PhD student with a passion for understanding how psychedelics reshape the brain.

His academic journey began with a degree in Biotechnology from the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. He then completed a traineeship in regenerative neuroscience at the GlowLab at the University of Zagreb. Following this, he pursued a Research Master’s in Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, where his fascination with the neurobiology of psychedelics developed.

Sergio was awarded the atai Fellowship for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics, which allowed him to join the Center for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics (CNP) at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School.

As a PhD student at the CNP, he specializes in fundamental research to investigate how natural and synthetic psychedelics, along with other neuroplasticity modulators, can drive structural and functional changes in the brain.

Beyond the lab, Sergio actively contributes to the psychedelic science ecosystem as a Scientific Dissemination volunteer at the OPEN Foundation.