New term – old story

Nature-connectedness, our subjective sense of our relationship to the natural world, is at an all-time low globally, and so is the health of our planet as well as our own. What we are experiencing is a vicious cycle of disaffection between mental suffering, environmental destruction, and further estrangement from the natural. How can we disrupt this cycle and turn it around? In this opinion piece, I argue that psychedelics can be used as a tool for turning a vicious cycle into a virtuous one. Psychedelics can be turned into “ecodelics”.

“Ecodelics” is a term coined by Richard Doyle in 2015, describing the power of psychedelics to induce ecological awareness and encourage eco-friendly behavior. The term might be new, but the idea is not. Throughout psychedelic history in the West, many believe that psychedelics are an essential tool for rekindling our relationship to nature and transforming our societies. This includes many prominent figures – from philosopher and ethnobotanist Terence McKenna in the 1980s to author and journalist Michael Pollan today.

Swiss chemist and discoverer of LSD, Albert Hofmann suggested that the deepest potential of psychedelics is the opening to a more ecological consciousness: “Alienation from nature…is the causative reason for ecological devastation and climate change. Therefore, I attribute the absolute highest importance to consciousness change.” But the story is much older than this – for many Indigenous cultures, such as the Mazatec people of Oaxaca, fostering a connection with the natural world has been an inherent feature of psychedelic use for millennia.

The counter-cultural hippie movement of the 60s and 70s demanded a radical shift towards environmental consciousness for the first time in Western history, and many believe it was fueled by LSD. The euphoria of the time ebbed off and the movement was oppressed, including through the 1971 War on Drugs Act. But could it be that the movement was crushed, not because it was powerless, but because it was too powerful in threatening the cultural and political status quo? The 60s and the present time are not two distinct events, they are two chapters of one story – and it seems that today, the story continues.

Growing momentum

Today, there is a lot of new momentum in connecting the psychedelic and environmental causes: the climate action movement Extinction Rebellion was formed thanks to a psychedelic experience, and so were many other environmental organizations and projects.

New organizations such as PSYCA – “Psychedelics for Climate Action” build global communities and actions around this idea. According to PSYCA founder Marissa Feinberg, “a consciousness shift is critical to catalyzing collective climate action.” Even in the business world, psychedelics are starting to make changes: researcher Bennet Zelner brought CEOs to Amsterdam to do psychedelics; as a result, their leadership styles shifted towards more empathy and purpose.

New scientific research into ecodelics

Western science is starting to grow interested in the connection between psychedelics and nature, with ecologist Sam Gandy and clinical psychologist Rosalind Watts trying to wrap their heads around it through research and practice.

Sample sizes are still small, but the emerging data is consistent. A 2022 paper found that psychedelic use predicted “nature relatedness” – a type of connection that goes beyond love or knowledge of nature and includes respect and affection for it even when it isn’t useful or aesthetically pleasing. It also predicted objective knowledge and concern about climate change, concluding that “there is a reliable association between psychedelic use and enhanced relatedness and empathy towards one’s environment.”

Another recent work on “psychedelically induced biophilia” highlights that this connection is “passionate and protective, even among those who were not previously nature-oriented”. Multiple meta-analyses have shown that nature-connectedness is a reliable predictor of a broad range of pro-environmental behaviors, regardless of political views. Just this month, a study found that intentional use of psychedelics can transform eco-anxiety into equanimity, resilience, and environmental action.

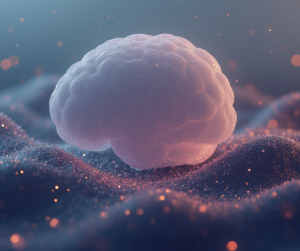

Why is this the case? Why should temporary, chemically induced experiences that create changes at the individual level contribute to problem-solving at the societal scale? At the University of Maastricht, a new research project on “psychedelics for planetary health” is seeking to answer this question: researcher Sarah Roche is preparing a study to illuminate the cognitive mechanisms that could link the psychedelic experience to ecological behavior.

Based on my personal journey from behavioral modeling for the climate transition, through burnout caused by climate anxiety and grief, to a renewed sense of agency, purpose, and hope brought about by psychedelic states, I propose three major mechanisms by which psychedelics could help us realize the changes we want: courage, presence, and connection.

#1 Courage

The critical decade to avoid dangerous tipping points in the climate system is running out fast, and unparalleled uncertainty is destabilizing us. The denial, distraction, polarisation, and conflict we see around the world are all expressions of being afraid. How can we avoid panic or depression to paralyze us at a time when we need to step up our game?

To perform the transformation that our physical realities demand from us, we need the type of consciousness that does not respond to change with fear. To enact meaningful behavioral change for a greater good in our own lives, let alone encourage it in our communities or nations, we must first develop the capacity to come eye-to-eye with the enormity of our loss and uncertainty. For many, the hesitation to engage in environmental problems like the climate crisis stems from a perceived incapability of handling grief and despair.

Psychedelics can allow us to open Pandora’s box and move through our challenging emotions, allowing those active in the cause to keep doing this important work, and those in denial or fear to become empowered. The existential fears caused by the state of our planet are not unlike the existential fears around terminal illness that psychedelics have been shown to treat very effectively. They show us the way to a type of awareness spacious enough to hold despair and active hope side by side, not letting fear paralyze us. Christiana Figueres, the “woman behind the Paris Agreement” explains how grounding herself in her difficult emotions was essential to generate her deep impact: “it is that being grounded in our emotions that generates deep clarity of what needs to be done; it puts two things side by side: yes, I am in deep pain, and es, precisely because of that I am committed to do everything within my sphere of influence.” In this way, our pain becomes fuel for our commitment.

This can be as big as organising a protest or changing one’s job, or as small as buying locally or having an honest conversation with a family member. No matter how big or small, the resolution to enact change often requires swimming against the stream. Finding the courage to challenge social norms is one of the most powerful interventions one can make today, and psychedelics are (in)famous for encouraging this through increased cognitive flexibility. They offer an experience of inner validity to one’s intuitive voice, a powerful trust in one’s own sense of right or wrong. This allows us to question all the social institutions we take for granted, and envision better ones.

#2 Presence

Much of the damage we do to the earth stems from a belief that joy and happiness will be attained through our endless chase of gratifying experiences. Cultural myths around scarcity, competition, and individuality have fostered a habit of prioritising instant gratification – even over our own deeper values. However, what makes us truly human at a deeper level is our unique ability to become mindful and present, to observe our impulses and yet choose to act in accordance with the human being we want to be.

This state of presence reconnects us to a sense of joy and abundance, training our ability to find beauty in the immediate and radiate a sense of care and possibility to those we interact with. In times as scary as ours, this is an essential skill set to remain resilient and engage in a compassionate, constructive, and transformative manner. Living with contentment in the present, even discomforts, such as taking a long train ride instead of a plane, can become gratifying experiences of mindfulness and solidarity, knowing that they are done for the greater good. A more profound sense of fulfillment then arises, one grounded in freedom, self-respect, and love. Psychedelics can be used as a powerful teacher for cultivating these very qualities.

A growing number of studies confirms that psychedelics can foster this heightened state of present-moment awareness, openness to experience, as well as non-reactivity – key components of mindfulness. Only when we notice our own behaviors – and only when we begin to identify more strongly with our values than our cravings – can we succeed in changing them.

#3 Connection

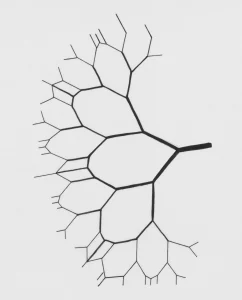

It is this shift in identity that I believe is at the core of the connection between psychedelics and the environmental movement. Psychedelic experiences can provide a direct, highly personal, and emotionally significant experience of oneness with the natural world. It is this emotionally significant experience of belonging, experienced in the body rather than the mind, that makes all the difference. “We’re all connected”, while obvious to the intellect as a physical reality – only hits home once it is directly experienced in a way that moves us. Johns Hopkins University researcher Roland Griffiths explains: “The core mystical experience is one of the interconnectedness of all people and things, the awareness that we are all in this together. It is precisely the lack of this sense of mutual caretaking that puts our species at risk right now.”

Psychedelics can alter our self-boundaries and increase our empathetic concern. By reducing the grip of our ego, they can open the doors for real love towards other humans as well as animals and plants, even those alive in the future – a process called “moral circle expansion”. A study by researcher Carhart-Harris and others confirms: psychedelics can cause “subtle shifts away from self-focus, individualism, a desire for financial success and competitiveness” towards more “intrinsically oriented cooperative, accepting, inclusive and communitarian values”. Harm to nature becomes harm to self. While this experience is temporary, for many it is so profound that it has a lasting effect on whom they care about. In this way, psychedelics can motivate us to orientate our lives towards the collective will.

The question remains whether individual action can truly make a difference for a predicament so globalized and complex as the environmental crisis. In Part 2 of this article, I will explore this question, based on the modeling results of my work as a behavioural specialist at the International Energy Agency (IEA). And I will expose ethical concerns and practical implications of psychedelics for planetary action: where lies the boundary between brainwashing and use with intention, and who can we turn to to learn how to use ecodelics in ethical ways?

Acknowledgements

The author expresses a special thank you to Georgia Kareola and Jasmine Virdi for their contribution.