Chris Letheby’s “Philosophy of Psychedelics” explores the relationship between the philosophy of psychedelics and the mechanisms of psychedelic therapy.

Through this curation of a few sections from chapters 7 and 8 of Letheby’s work, the reader is invited to think along.

The Comforting Delusion Objection to Psychedelic Therapy

Central to Letheby’s book is the provision of an appropriate response to the ‘Comforting Delusion Objection to psychedelic therapy’ — it says that psychedelics induce their salutary psychological effects mainly by inducing metaphysical beliefs that are comforting but probably false.

Is it the case that psychedelics merely create comforting delusion? Are therapeutic outcomes a result of false metaphysics? Let’s take a step back.

a transient and dramatic experience that Uncovers New Modes of Perception and Being

Source: Unbinding the self — Philosophy of Psychedelics by Chris Letheby, Chapter 7 — p. 124-5

Letheby starts this chapter by pointing to the aim of many psychiatric treatments:

“Many psychiatric disorders feature deleterious changes to self-related beliefs and many treatments aim at “resetting” these beliefs — at changing them for the better.”

“Phenomenologically speaking, the interpersonal world simply is threatening, or the self simply is powerless: they are not merely believed to be so.”

Psychedelics’ ability to induce a transient and dramatic experience may become relevant in a similar therapeutic process of shifting habitual beliefs and identity:

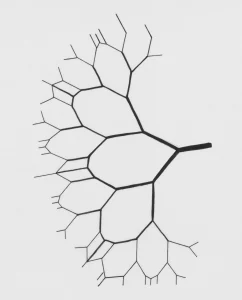

“Through radically altered forms of self-experience, subjects discover the contingency, mutability, and stimulatory nature of their own sense of identity and habitual modes of attention. They learn directly that there are other ways of being and other ways of seeing because their ordinary ways of being and seeing result from a malleable modeling process.

By disrupting the neurocognitive substrates of the brain’s high-level beliefs, psychedelics can change this situation transiently but dramatically resulting in:

1. Subjects experiencing new phenomenal worlds inconsistent with and previously precluded by those beliefs.2. As a corollary, the beliefs themselves become phenomenally opaque as their representational nature becomes more vividly apparent.”

Hallucination or Revelation? Navigating the Epistemic Uncertainty of Psychedelic States

Source: Epistemology — Philosophy of Psychedelics by Chris Letheby, Chapter 8 — p.160-2

However, how can one be certain that these newly experienced phenomenal worlds are something to be learned from?

”Some psychedelic users claim sincerely to encounter genuinely existing disembodied entities, spirit realms, and transcendent Grounds of Being.”

Should those claims simply be rejected?

“On principled philosophical grounds, naturalists reject these claims as arising from compelling drug-induced hallucinations — misrepresentations of reality.”

“The key to understanding the epistemic profile of the psychedelic state comes from Andy Clark’s dictum that prior knowledge in the predictive brain is always both constraining and enabling.”

- “Certain epistemic benefits available in the sober state become unavailable, such as rational and critical thought and the ability to deploy much prior knowledge.

- Others unavailable in the sober state become available — principally, the opportunity to access information otherwise filtered out by overweighted priors, as well as the ability to represent certain kinds of information in novel and epistemically useful formats.”

is a sense of certainty epistemically justified?

”A second guiding principle comes from Jennifer Windt’s observation that ‘phenomenal certainty — the experience of persuasion or knowing — is not the same as epistemic justification’.”

“Having a psychedelic experience in which some proposition P seems true, accompanied by a strong phenomenal feeling of certainty, does not constitute sufficient justification for believing that P is true.”

Chris Letheby’s Conclusion “Epistemic Innocence”

“Many psychedelic states are, in Lisa Bortolotti’s parlance, epistemically innocent. This means that despite having real epistemic flaws, they also have significant epistemic benefits that are not available by any alternative means. In sum, psychedelics’ overall epistemic profile is neither as dire as some skeptical naturalists might assume, nor as pristine as some entheogenic enthusiasts would like.