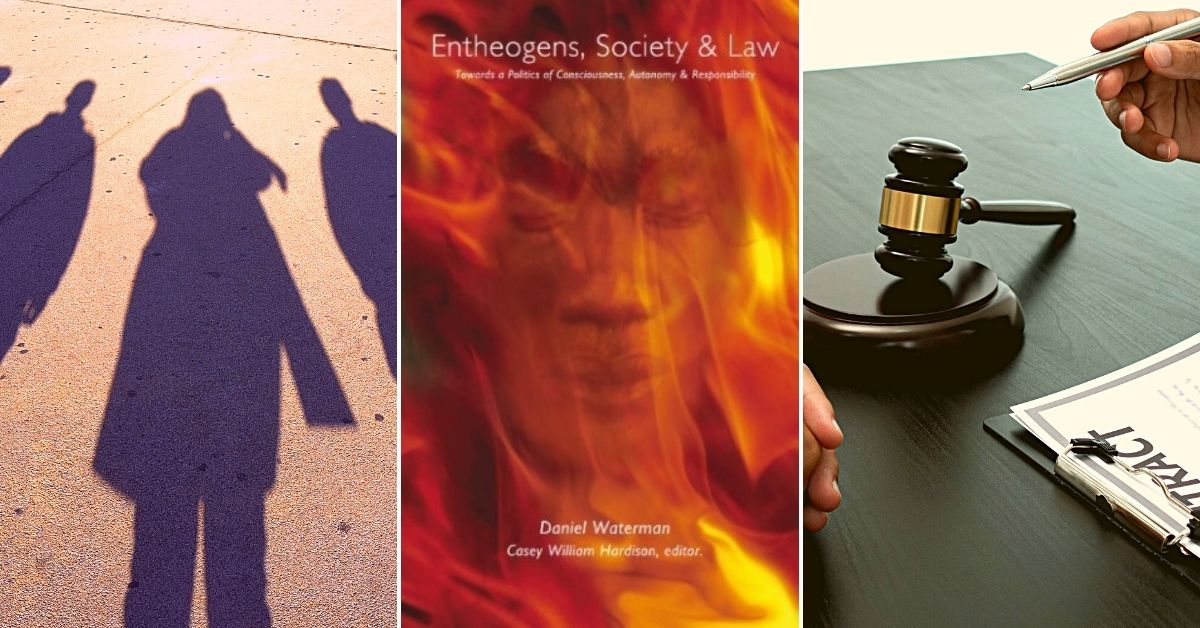

Entheogens, Society & Law: Towards a Politics of Consciousness, Autonomy & Responsibility by Daniel Waterman, edited by Casey William Hardison, Melrose Books, 2013.

Psychoactive substances are strongly intertwined with society. They produce highly subjective effects, and are simultaneously highly politicized. Likewise, the cultural and societal context determines to a large extent the content and interpretation of the experience. Daniel Waterman’s ‘Entheogens, Society & Law’ is about this interplay. In his book, he discusses the interrelation of consciousness and ethics and argues that a reconsideration of regulatory choices is necessary for a more beneficial way of dealing with these substances. It is a broad-ranging book that addresses a large variety of subjects.

After a brief personal introduction, Waterman shows how the way we talk about psychoactive substances influences not just the experience, but also its interpretation and whether the outcome is beneficial. Similarly, he argues that law stratifies such beliefs we hold about psychoactive substances and that this in turn influences both the way we see them and the way we see ourselves.

The second chapter is an elaboration on the different ways in which psychoactives have been conceptualised throughout history, and the results of these conceptualisations. Drugs and drug users have many faces and Waterman gives a thorough analysis of all the different roles they play within society, both positive and negative. He shows the complexity of these concepts and how many different interpretations are possible. This analysis contributes to a fuller understanding of psychedelics and the psychedelic experience and has not been published elsewhere to such an extent.

In the third chapter we find a large section on the work of Professor Jan Bastiaans, a Dutch psychiatrist who treated people suffering from what was then called ‘concentration camp syndrome’ with LSD. Concentration camp syndrome would later be incorporated into the more recent category PTSD. Bastiaans was educated in classical psychoanalysis and went on to apply these techniques in psychedelic therapy. In the late eighties, Bastiaans would come into disregard for not maintaining proper archives, preventing anyone from evaluating the effectiveness of his treatment. Although largely based on the work of Stephen Snelders and the biography by Bram Enning, this book provides one of the first extensive reviews of Bastiaans’ work in English and it is a welcome addition to the historical study of psychedelic research.

The book continues with a section on the transpersonal psychology of Stanislav Grof. While a giant in the field, Grof is not often compared and contrasted to his predecessors, starting with Sigmund Freud and his heirs Carl Jung, Otto Rank and Wilhelm Reich, and with peers like Abraham Maslow. This comparison helps us understand Grof as part of a lineage of psychoanalysts. By placing Grof in this lineage, we can see how he both learned from his tradition and elaborated upon it by working intensively with LSD in the Czech Republic and the US.

In his final chapter, the author shows how the transpersonal experience is central to a variety of religions and argues that these experiences help people integrate on a personal and social level. In that sense, Waterman posits, they are the epitome of ethics itself, because they require us to take responsibility for our actions on a grander scale. Conversely, prohibiting (some ways to achieve) such experiences prevents people from becoming more conscious and, consequently, more compassionate and kind.

The book is not neutral and doesn’t claim to be. Both author and editor are outspoken proponents of cognitive liberty and the freedom to alter consciousness. However, their claims are supported by relevant research and their political stance is rooted in a strong tradition of scientific research and philosophical thought, although conservatives might label it as radical.

The book does have flaws, the biggest of which is that it is often unclear where the argument is taking the reader. Because many subjects are dealt with extensively, it is easy to lose track of the line of reasoning. More elaboration on how digressions fit in with the general argument would have allowed for a more focused book. As it stands, the book’s topics, while interesting in themselves, often remain unconnected. The effect is that the reader has to piece the argument together himself, which makes for a sometimes challenging read, requiring a strong focus on the part of the reader.

Another flaw is that some ideas are explained in both footnotes and in the main text. This unnecessary repetition, along with some mistakes and sloppiness in the footnotes, stain an otherwise well annotated text. Both these issues should have been mended in the editorial process.

But there are enough diamonds in the rough. This book broadens one’s perspective well beyond the boundaries of what is normally found within the literature on psychedelics. The author discusses many questions that are usually left unanswered and still manages to fit everything together. It is a book for those interested in the interplay between how we think about altered states and the substances that induce them, how this influences the experience, and how these feedback loops influence the way we deal with them as a society.

Buy this book at bookdepository.com and support the OPEN Foundation.