Key takeaways

The current “Psychedelic Renaissance” represents a new phase in the use and perception of psychedelics, distinct from earlier waves in the 1950s-70s. Today, alongside renewed scientific interest and media coverage of their therapeutic potential, significant private investment is driving the emergence of a multi-billion-dollar psychedelic mental health industry.

Key stakeholders in this evolving landscape include:

- Users seeking safe, legal access

- Patients seeking treatment

- Indigenous and religious communities striving for recognition and the right to maintain their traditions

- The scientific community advancing research

- A new and influential actor—private investors, whose primary interest lies in commercialization and profit.

Acknowledging the contributions of Indigenous groups, whose ancestral knowledge underpins much of psychedelic medicine, is essential. While some initiatives promote open-source science and benefit-sharing, achieving true reciprocity and ethical engagement remains an ongoing challenge.

What is the “Psychedelic Renaissance”?

Much has been written about the historical precedents of the so-called “Psychedelic Renaissance”. From promising psychiatric drugs in the 1950s, to counterculture agents in the 60s and the 70s condemnation. Now, this “renaissance” appears to be heavily focused on their therapeutic interest again, both from the scientific community and mainstream media, adding tho, a new factor to it – the bulky private investments being made, that created a multi-billion-dollar mental health industry.

Who are the main actors interacting with psychedelics?

- Users – with their many different epistemologies for use. Whether for recreational use, creativity, or self-development. It’s important to acknowledge that the differences between these groups are significant; they’re being placed in the same category here only because they are not the primary focus of this article);

- Patients;

- Indigenous communities;

- Religious communities;

- Scientific community;

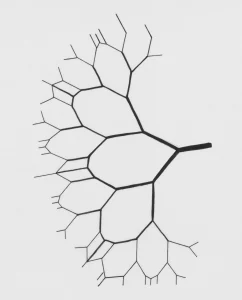

- Private investors – such as corporations and venture capitalists. As Jacob Aday, et al. write in their paper, “the main focus of companies in the psychedelic sector can be broadly grouped into: (1) drug discovery and development; (2) novel formulations and routes of administration; (3) manufacturing and synthesis; (4) treatment centers and wellness clinics; (5) consumer packaged goods and adult use; and (6) adjunct technologies” (p.150).

Differently from 1960, the “Psychedelic Renaissance” brought increased interest in commercialization of psychedelics and also treatments. In the 60s we did have Sandoz, producing psilocybin and LSD, after Albert Hofmann synthesized them, but its role, it appears was more as to support scientific and psychiatric research, rather than profit.

So what are these actors’ main interests in the psychedelic renaissance?

- Users – one could argue, the safe and legal access;

- Patients – healing;

- Indigenous communities and religious communities – preserving their traditions and identity;

- Scientific community – in a way, fulfil the interest of the patients, by providing healing;

- Private investors – profit;

Private investors are typically profit-driven. Their primary goal is to create and expand a market for psychedelics. Markets tend to favor efficiency – where the most effective products, companies, or services succeed – and competition, which is fueled by the freedom to innovate and outperform others.

So before asking how these actors are benefiting, we should ask how would they benefit?

And the answer to that is simply – if their interests are met. So taking on the answers from the last question, the answer is simply if they got that. The answer is only different for one of these actors – the indigenous communities. Why is that?

This is related to the history and origins of psychedelic use for healing. The concept behind the commercialization of psychedelics for healing lies in ancient plant knowledge safeguarded, often at great risk, by indigenous communities. Communities who have used mushrooms, ayahuasca, peyote, and other plant medicines in spiritual and healing practices for millennia. Communities whose use was heavily suppressed, in the first place, by colonial forces.

In Mexico for instance, mushrooms have been prohibited since the 16th century. Most likely many of the groups using psychedelics were in fact extinct. But due to their resilience, some have continued to use them in traditional ceremonies, to this day. In fact, the Western World was introduced to this, back in 1950’s when Valentina Wasson, a mycology expert, and her husband, R. Gordon Wasson attended a Mazatec ceremony in Mexico led by Maria Sabina, and extensively wrote about it in LIFE magazine and several newspapers in the US. Some sources argue that the shaman never actually consented with her identity being revealed, as this later caused great misery – the peacefulness of her small village was disrupted by tourists wanting to Seek The Magic Mushroom, which led the villagers to turn against her. The ethical implications of publicly sharing Indigenous knowledge without her consent or adequate contextualization, to Wassons’ benefit and her detriment resembles in itself the colonial dynamics and remains an important topic of discussion.

So, coming back to the answer of – how would psychedelic actors benefit? – now we can say, that the Indigenous Communities would benefit if one, they would be able to practice their traditions without the risk of prosecution and criminalization; but also, if they got a fair acknowledgment for a practice that they first started, remembering that some of these substances are often native to indigenous land – the case of Ibogaine, the root from Gabon, now used to treat post-traumatic stress disorder – “Most iboga and ibogaine used by clinics around the world originates from plants poached from Gabon’s forests and smuggled out of Cameroon.”.

We can finally ask then, how are these actors benefiting?

- Users

Not much has been done by governments towards providing safe legal access; it is worth mentioning the work of some harm reduction NGOs, like Kosmiscare in Portugal, that are testing substances freely and anonymously. Additionally, some countries legalized ayahuasca (Brasil, Costa Rica, Mexico, Peru).

- Patients

Countries, like Australia and Switzerland, legalized these therapies, with certain psychedelics. In some other countries, the “off label” use of Ketamine allows private clinics to treat conditions like Treatment Resistant Depression (TRD) and burn out. Also, the flourishing clinical trials all over the world offer a possibility for patients to be treated this way.

- Indigenous communities and religious communities

Some national and international legal advancements are being made towards recognizing the importance of psychedelic substances for these communities. National legal protections for ayahuasca use in specific religious ceremonies; UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Article 24), affirming the right to traditional medicines.

- Scientific community

With growing attention on the potential benefits of these substances, more funding is being allocated to research them. However, substances like LSD remain classified as having no recognized medical use, despite scientific studies increasingly showing evidence to the contrary.

- Private investors

Venture capitalists and pharmaceutical companies are increasingly investing in the commercialization of psychedelic substances. Estimates suggest the psychedelic market could reach USD 11.82 Billion by 2029, driven by psychedelic companies, such as Compass Pathways and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. This commercialization introduced a profit-driven model that is broadly marginalizing the very cultures that have safeguarded psychedelic knowledge for centuries, by submitting patents on compounds and treatment methods.

A patent is a legal right granted by governmental agencies that gives an inventor or company exclusive ownership over an invention for a set period. Compass Pathways, for instance, currently holds ten patents, in many different countries. The company started in 2015 as a nonprofit to support research on psilocybin for cancer-related distress. In 2016, they launched a for-profit company, Compass Pathways Technologies Ltd to manufacture psilocybin for research and benefit from tax breaks otherwise not available to non-profit organizations. By 2017, they shut down the nonprofit, leading to criticism as some felt they used the charity’s work for profit. In 2020, they became the first psychedelic company on the Nasdaq stock exchange, reaching a $1.2 billion value (Aday, et al., 2023).

Pharmaceutical companies have been justifying patents by citing the high costs of clinical trials and regulatory approvals. However, this reasoning tends to ignore the fact that the foundational knowledge of psychedelic medicine originates from Indigenous cultures in the first place.

Then, what is needed to advance this field in a responsible way?

Open source science

Some individuals (such as Alexander Shulgin) and organizations (like Open Foundation), that gave significant contributions to the field, promote open-source psychedelic science, rejecting patents in favor of freely sharing research to prevent monopolization.

Benefit-Sharing Initiatives

Organizations such as Chacruna Institute launched the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative (IRI) a decolonial network with the intent to “Give back to Indigenous Communities” by creating a pool of funds to support Indigenous grassroots initiatives from food security and environmental health, to economic and educational support. In their 2023 annual report they add “those who do invest do not seem interested in contributions to Indigenous communities”.

Another example is the biopharmaceutical company – Journey Colab. Founded in 2020 to develop psychedelic treatments for addiction with mescaline, came up with a benefit-sharing mechanism — Journey Reciprocity Trust. The Trust holds 10% of the company’s founding equity and is “designed to share the value generated by the company’s success with Indigenous communities that have traditionally used psychedelics”. But as of the latest updates (late 2023/early 2024), no funds or equity has been distributed, raising some criticism of indigenous washing.

So, although this is a complex question to answer, a good starting point is to acknowledge the role of Indigenous communities as the original stewards of much of our knowledge around psychedelics. It’s crucial to ensure they are not marginalized or ignored in these conversations. Additionally, recognize that there is still a need for major investors to demonstrate genuine commitment to decolonial practices, equitable benefit-sharing, and honoring the origins of these powerful medicines.

References

- Aday, J. S., Barnett, B. S., Grossman, D., Murnane, K. S., Nichols, C. D., & Hendricks, P. S. (2023). Psychedelic Commercialization: A Wide-Spanning Overview of the Emerging Psychedelic Industry. Psychedelic Medicine (New Rochelle, N.Y.), 1(3), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1089/psymed.2023.0013

- Spiers, N., Labate, B. C., Ermakova, A. O., Farrell, P., Romero, O. S. G., Gabriell, I., & Olvera, N. (2024). Indigenous psilocybin mushroom practices: An annotated bibliography. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 8(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2023.00297

- Brandessence Market Research. (2023, January 30). Psychedelic drugs market to reach USD 11.82 billion by 2029. PR Newswire. Retrieved from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/psychedelic-drugs-market-to-reach-usd-11-82-billion-by-2029–brandessence-market-research-301720168.html

- Celidwen, Y., Rever, C., & Mihaylova, I. (2022). Indigenous reciprocity and ethical engagement in psychedelic medicine. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 865032. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.865032

- Ramstedt, M. (2020). Normative pluralism and justice after multiculturalism. In H. Hydén, R. Cotterrell, D. Nelken, & U. Schultz (Eds.), Combining the Legal and the Social in Sociology of Law (pp. 125–140). Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Vice. (2021). Is it possible to create an ethical psychedelics company? Vice News. Retrieved from https://www.vice.com/en/article/is-it-possible-to-create-an-ethical-psychedelics-company