We are like islands in the sea, separate on the surface but connected in the deep – William James

One of the most fascinating findings coming from the scientific literature on psychedelics is their ability to drastically alter our beliefs and worldview. These form the basis of how we relate to ourselves, each other, and the world. As a result, they determine how we attach meaning to our lives and whether we ultimately feel happy, sad, or depressed. Our beliefs and worldview can, in short, be considered as one of the most important aspects of who we are and how our lives unfold.

The current prevailing worldview in Western society to which most of us pledge allegiance is that of materialism. I am not referring to materialism in the consumerist sense, wherein the main preoccupation of the human being is the pursuit and obtainment of things, but materialism from the viewpoint of metaphysics, the branch of philosophy that is concerned with the study of the fundamental nature of reality.

Bernardo Kastrup, one of the speakers at ICPR 2022, challenges the current worldview of metaphysical materialism. Specifically, he proposes analytical idealism as an alternative, the notion that reality is essentially mental and inseparable from mind. Bernardo has been leading the modern renaissance on metaphysical idealism for the past ten years and is considered one of the most energetic, diverse, and original thinkers alive today.

The story of how Bernardo came to idealism is truly fascinating. For those who are interested, I highly recommend two podcast episodes (listed below) in which he explains how he arrived at this particular understanding of metaphysics. In short, Bernardo started his career as a computer engineer, working for some of the biggest and most important companies in the world, including the Dutch company ASML, the world’s leading computer chipmaker for the semiconductor industry, and the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) that operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world (i.e., the Large Hadron Collider).

Despite these prestigious positions, Bernardo always remained a philosopher at heart and was thus concerned with the bigger questions: “What is life? Where do we come from? What happens to our consciousness after we die?” More than anything, he pondered endlessly as a computer engineer on the possibilities and limitations of artificial intelligence: “If you put enough elements of a computer and chips together to aggregate computing power, when will it become conscious? More so, can it become conscious?”

Materialism and The Hard Problem of Consciousness

The unanswered question refers to a notorious problem that has been troubling scientists and philosophers alike for decades. It was first coined as ‘The Hard Problem of Consciousness’ by Australian philosopher David Chalmers in his famous essay Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness, which has been declared as the second most important unanswered question in science by Science. According to Bernardo, it should have been number one.

Before we continue, let’s first briefly discuss what materialism is all about. This way we can better comprehend the Hard Problem.

Metaphysical materialism states that all of reality is composed of a small set of fundamental subatomic particles, which are described in the ‘Standard Model’ of particle physics. These particles are the basic building blocks of nature and responsible for the character and behaviors of all known phenomena, from the chair you are sitting on to the entirety of the Milky Way, to your body and loved ones, and of course your mind.

Materialism assumes that these subatomic particles are “dead” and, therefore, absent from consciousness. Now here is the rub: “How do you eventually get consciousness simply by arranging ‘dead’ subatomic particles together?” Alas, we have arrived at the Hard Problem of consciousness. Bernardo calls it a sore on the foot of materialism. In fact, it is such an obstinate problem that materialist philosophers, such as Daniel Dennett, have been accused of ‘explaining it away’.

How do you eventually get consciousness simply by arranging ‘dead’ subatomic particles together?

Other famous neuroscientists, such as Christof Koch, remain hopeful and claim that it is only a matter of time before we resolve the Hard Problem. Koch initiated his quest alongside molecular biologist turned neuroscientist and Nobel Prize winner Francis Crick in the 1990s. Most of all, their primary objective was to discover the neural correlates of consciousness (NCCs), which refers to the “the minimum neuronal mechanisms jointly sufficient for any one specific conscious experience.”

Similar to philosopher Daniel Dennett, consciousness has in their view a mechanistic basis and is ultimately a scientifically tractable problem. So long as we keep collecting more data about the inner workings of the brain through state-of-the art neuroimaging techniques and aggregate this over the years, we will eventually find the much sought after NCCs. The phenomenon of consciousness is, after all, produced by an assembly of dead subatomic particles that we would call a human brain. Consciousness is material brain processes at work.

Exactly how these material brain processes and the various mechanical movements of particles are accompanied by inner life remains, however, “a question left unanswered by materialism”, states Bernardo in Why Materialism is Baloney – How true skeptics know there is no death and fathom answers to life, the universe and everything.

It is here that Bernardo firmly states that such (scientific) pursuits are – and will remain – futile. We cannot solve the Hard Problem through science because of the simple fact that science cannot look at what nature is – science can only look at what nature does: “The scientific method allows us to study and model the observable patterns and regularities of nature […] But our ability to model the patterns and regularities of reality tells us little about the underlying nature of things”, writes Bernardo.

Tackling the Hard Problem: Idealism to the Rescue

To tackle the Hard Problem, we need to approach it through metaphysics, it being the branch of philosophy that concerns itself with the study of the fundamental nature of reality. Metaphysics looks at what nature is.

Now, Bernardo does not actually “solve” the Hard Problem, but rather circumvents it through his metaphysical framework of idealism. In fact, he suggests that there is no problem at all; it is only a problem when we believe the metaphysics of materialism to be true. And so long as we adhere to the materialist worldview, we keep misconstruing our conception of reality through a flawed conceptual framework that is ultimately nonsensical and self-defeating.

As I was reading about the Hard Problem and delved more and more into the framework of idealism, a quote from Einstein came to mind that perfectly encapsulates the current predicament: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” Within the metaphysical framework of materialism, the Hard Problem cannot possibly be solved. It is created within a certain mode of thinking, a mode of thinking that is, according to Bernardo, the wrong one.

The Hard Problem is only a problem when we believe the metaphysics of materialism to be true.

So what, then, is idealism? As mentioned before, idealism consists of the notion that mind and reality are inseparable. Put slightly differently, it states that ‘mind’ is the medium of reality, not ‘matter’. This sounds rather abstract and confusing at first, because mind is generally referred to as something we use (although I have my doubts about some individuals) or lose. We see this particularly reflected in our everyday language: “use your mind for once!” or “he has lost his mind!”

Within the metaphysical framework of idealism, however, the mind is defined as something entirely different. In the opening of Chapter 3 in Why Materialism is Baloney, Bernardo provides a “most natural and obvious answer” to the question of what ‘mind’ signifies within the framework idealism: “Mind is the medium of everything that you have ever known, seen, or felt; everything that has ever meant anything to you. Whatever has never fallen within the embrace of your mind, might as well have never existed as far as you are concerned. Your entire life and universe – your parents and the people you love, your first day at school, your first kiss, every time you were sick, the obnoxious boss at work, your dreams and aspirations, your successes, your disappointments, your worldview, etc. – are and have always been phenomena of your mind, existing within its boundaries.”

Yet this description of mind within the framework of idealism remains just that: a description. Again, I want to emphasize here that in order to intuitively understand, or “grok” (to borrow from Bernardo’s lexicon), requires a different mode of thinking. Speaking from personal experience, this is an arduous process, particularly because the worldview of materialism is so firmly ingrained within us. It is a firmly established belief system accompanied by a habitual mode of thinking that is often considered infallible.

Mind is the medium of everything that you have ever known, seen, or felt; everything that has ever meant anything to you. Whatever has never fallen within the embrace of your mind, might as well have never existed.

To avoid eating the menu, we can use metaphors to get an initial taste of idealism. Fortunately, Bernardo provides no shortage of these in Why Materialism is Baloney – a triumphant feat on par with the wit of Alan Watts. In my view, the most intuitive analogy to start off with when trying to “grok” idealism is the whirlpool.

Whirlpools Within the Lake of Mind

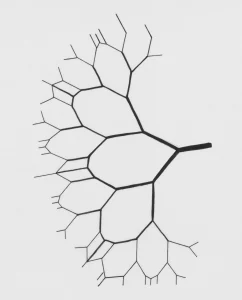

Consider ‘mind’ as a lake of water. When this lake is still, water is flowing along freely without any hindrance. The water is not localized. Now, imagine a small whirlpool within the lake. All of a sudden, there is an identifiable pattern that assembles the water molecules in place within the lake. In other words, the whirlpool reflects a pattern that localizes the flow of water (see Figure 1).

We are able to point at this pattern and say: “Here is a whirlpool!” Other water molecules that are not localized through the whirlpool are ‘filtered out’ – they are kept away by the particular dynamics of the whirlpool. From this, Bernardo makes two observations regarding the whirlpool metaphor, namely that 1) the whirlpool reflects a localization of water within the lake and 2) that there is a ‘filtering out’ of the other remaining water molecules.

Figure 1

The whirlpool in a lake is a metaphor for a brain in the medium of mind (from Kastrup, 2014)

These observations lead to the following conclusion, namely that “there is nothing to the whirlpool, but the lake itself.” It is important to remember this statement in the next few paragraphs, because it contains the essence of idealism. Once more, the only thing that the whirlpool reflects is a very specific pattern of water that has been localized within the lake. Ultimately, it is all water. It is all one.

There is nothing to the whirlpool but the lake itself.

Bernardo mentions the brain as something very analogous to the whirlpool in the lake. More specifically, he talks about the brain as “an image [pattern] in mind, which reflects a localization of contents of mind.” And just like there is nothing to the whirlpool but the lake, there is nothing to the brain but mind itself. Within the metaphysics of idealism, the brain represents an identifiable pattern of the localization of mind. Similar to the whirlpool within the lake, we can point to the brain within the medium of mind and say: “Here is a brain!” And just as the whirlpool captures water molecules from the lake, the brain assembles subjective experiences from the medium of mind and ‘filters out’ experiences of reality that under ordinary circumstances do not fall within its boundaries.

There is nothing to the brain but mind itself.

Consider the following. Would you say that a whirlpool causes water? Or that flames are the cause of combustion? What about lightning being the cause of electric discharge? My guess is probably not. In fact, you would be rather perplexed when someone gives you these presuppositions: “Of course a whirlpool does not cause water. It is exactly the other way around; the water, or the lake, is the very thing that causes the whirlpool!” Naturally, the whirlpool and water are very much related to each other, but the whirlpool only represents a “partial image” of the whole process that is lying underneath it.

And the same can be said of the brain. It too represents a partial image within the broader medium of mind. According to Bernardo, saying that “the brain generates mind is as absurd as to say that a whirlpool generates water!” (italics added).

Understanding the brain to be a partial image within the broader medium of mind eliminates the Hard Problem entirely, because the aforementioned NCCs can now be interpreted differently. Yes, there still exists a clear and obvious relationship between brain states and someone’s state of ‘mind’, but now the former can be seen as a partial image of the latter. As Bernardo concludes: “The brain is an experience, an image in mind of a certain process of mind.”

What materialism is trying and claiming to accomplish is the impossible. It maintains that the brain is the very thing that causes consciousness and the plethora of subjective experiences that go along with it. But if you understand just a little bit of what has been presented so far, you can begin to see that this is a complete non sequitur. It does not follow that consciousness is the cause of brain processes, as one would similarly not infer that combustion and water are respectively caused by flames and whirlpools. Trying to fix it only results in what is keenly illustrated on a subreddit that creates some hilarious memes of Bernardo and idealism.

Of course, it would be unfair to entirely negate materialism based on just this metaphor, albeit it being a very useful one. This is where psychedelics come in, as their effects on the brain help make sense of this metaphor.

Brief Peeks Beyond: The Acute effects of Psychedelics on the Human Brain

In the past decade, Bernardo has written extensively about the acute effects of psychedelics on the human brain. More specifically, he has provided evidence of how neuroimaging studies seem to support the tenets of idealism – much to the dismay of other materialist neuroscientists, which include previous ICPR speakers as Enzo Tagliazucchi and Robin Carhart-Harris.

To be clear, Bernardo never suggested “malicious intent.” Rather, the intention was to emphasize how “paradigmatic expectations can make it all too easy to cherry-pick, misunderstand and then misrepresent results so as to render them consistent with the reigning [materialist] worldview.” Indeed, it is a clear example of how materialism permeates the culture and how unaware we are of our philosophical presuppositions.

In general, neuroimaging studies examining the acute effects of psychedelics on the human brain demonstrate that there is an inverse relationship between brain activity and subjective experience. Wait, what? Yes, you read that correctly. Psychedelic substances are found to reduce brain activity, rather than increase it. Such results vehemently oppose the intuitions of materialism. After all, it is brain activity itself that is supposed to constitute subjective experience: “consciousness is brain activity.” How else are we going to find the NCCs?

Down below follows a summary of two important neuroimaging studies and Bernardo’s interpretations of their results, which led him to conclude that the evidence thus far supports idealism.

The first study examined the neural correlates of psilocybin. According to Bernardo, this study was “extremely well designed” as it countered the “uncertainties of measuring brain activity with an fMRI scanner.” Here, he is alluding to the fact that the researchers used two ‘signals’ in determining brain activity, namely arterial spin labeling (ASL) and blood-oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). More specifically, ASL is a non-invasive fMRI technique for measuring cerebral blood flow (CBF): the amount of CBF indicates the amount of brain activity. On the other hand, BOLD measures the difference between oxygenated and deoxygenated blood in various brain regions that indicates the level of metabolism. Ultimately, it is the amount of metabolism which indicates the amount of brain activity in a given brain region.

With both these measures, here is what the authors from the psilocybin study reported: “we observed no increases in cerebral blood flow in any region” (italics added). Even more ‘alarming’: “the more the drug deactivated the brain, the more intense were the subjective experiences reported by the subjects” (italics added).

Reading further into the study, results become particularly worrisome for materialists when study participants made report of having had extremely rich subjective experiences, which included “geometrical patterns”, “extremely vivid imagination”, “seeing their surroundings change in unusual ways”, and having experiences that feature a “dream-like quality.”

Bernardo summarized the findings in one of his many blog posts and stated: “the brain largely goes to sleep. Who, then, is having the trip? It doesn’t seem to be the brain.”

Neuroimaging studies examining the acute effects of psychedelics on the human brain demonstrate that there is an inverse relationship between brain activity and subjective experience

Fast forward four years later and another study came out that examined the neural correlates of LSD. This time the findings received much more attention from the public and was covered by prestigious media outlets, such as The Guardian and CNN. Bernardo responded to this “fanfare” and explained to his readers how they are being “subtly deceived (again).” Because, similar to the psilocybin study, results yet again demonstrated observed reductions of brain activity across the entire brain (see Figure 2). As you can clearly see, there is a whole lot of blue. In fact, everything is blue which indicates reductions in brain activity.

Now, to be fair, the authors from the LSD study did find one small inconsistency when comparing findings to the psilocybin study. Apparently, there were results that indicated increases in CBF in the visual cortex of the brain when LSD was compared to placebo (see third row Figure 3). Such a finding would indeed support the view of materialism, i.e., more activity in the brain equals more subjective experience.

Figure 2

Brain activity as determined by magnetoencephalography

Yet, the authors from the LSD study concluded that the observed localized increases in CBF were possibly the result of measurement artifacts: “one must be cautious of proxy [indirect] measures of neural activity (that lack temporal resolution), such as CBF or glucose metabolism, lest the relationship between these measures, and the underlying neural activity they are assumed to index, be confounded by extraneous factors, such as a direct vascular action of the drug.”

Figure 3

Cerebral blood flow as determined by ASL

This is why the authors opted to put more emphasis on findings from Figure 2, as it represents the results of magnetoencephalography (MEG). This is another widely used functional neuroimaging technique for mapping brain activity. As opposed to indirect measures such as BOLD and ASL, MEG represents a direct measure of neural activity. Naturally, the LSD study authors concluded that MEG: “should [thus] be considered [as] more reliable indices [measures] of the functional brain effects of psychedelics” (italics added).

Of course, these were only two studies that examined the acute effects of psychedelics on the brain. But as many of you probably know, the psychedelic renaissance has been on full throttle in the past years. As both Bernardo and Prof. Edward F. Kelly alluded to in an opinion piece on Scientific American: “these unexpected findings have since been repeatedly confirmed with a variety of psychedelic substances and various measures of brain activity” (see 2013, 2015, 2016, and 2017).

Let us now transpose these neuroimaging findings in context of the whirlpool metaphor. Remember how we said that both the whirlpool and brain analogously represent an identifiability pattern, or image, within the broader medium of the lake and mind, respectively? And remember how we also said how they both reflect a localization and filtering of the contents of mind, which led us to conclude that there is nothing to the brain but mind itself? Here is what psychedelics seem to do.

Psychedelics perturb the dynamics of the brain to such a degree that there is a non-localization of the contents of mind (i.e., subjective experiences that are, under ‘normal’ circumstances, assembled by the brain). But now, by bringing psychedelics into the mix, subjective experiences from the medium of mind are suddenly no longer filtered out. The whirlpool stops existing, water molecules are able to flow along freely, and thus become one with the lake. Analogously, the brain stops “existing” as activity goes down that results in a bombardment of subjective experiences (e.g., “extremely vivid imagination” as the psilocybin study participants reported). Ultimately, the contents of mind that were, under ‘normal’ circumstances, assembled by the brain become one with the medium of mind. To put it in Aldous Huxley’s words, the psychedelic experience can bring about the realization that “each one of us is potentially ‘Mind at Large’.”

The contents of mind that were assembled by the brain become one with the medium of mind

A sweet moment of irony, particularly for Bernardo, is how the authors from the psilocybin study unintentionally hinted toward the whirlpool metaphor themselves by mentioning Aldous Huxley’s metaphor of the reducing valve: “This finding is consistent with Aldous Huxley’s ‘reducing valve’ metaphor … which propose[s] that the mind/brain works to constrain its experience of the world.”

For people who are unaware, the reducing valve metaphor is a result of Huxley’s experience with the psychedelic substance mescaline. He reported his experiences in The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell. Huxley’s description of the brain as a reducing valve – and its similarities with the whirlpool metaphor – become immediately apparent in the following passage: “The suggestion is that the function of the brain and nervous system and sense organs is in the main eliminative and not productive (italics added). Each person is at each moment capable of […] perceiving everything that is happening everywhere in the universe. The function of the brain and nervous system is to protect us from being overwhelmed […] by shutting out most of what we should otherwise perceive or remember at any moment, and leaving only that very small and special selection which is likely to be practically useful.” To clarify here, when Huxley mentions that the brain’s job is “to protect us from being overwhelmed” seems to be analogous to the localization of the contents of mind. The same can be said for how subjective experiences are “shut out” and the filtering out process in the whirlpool metaphor.

Finally, these so-called peak experiences associated with psychedelics are not only reserved to dedicated psychonauts. In fact, “there is a broader pattern associating peak subjective experiences with reduced blood flow to the brain”, says Bernardo. This is further exemplified in Why Materialism is Baloney and another academic article in which he lists a host of findings from different domains (e.g., hyperventilation, meditation, gravity-induced loss of consciousness, cerebral hypoxia, cardiac arrest, and even brain damage). All seem to corroborate the phenomenon that less blood flow equals richer subjective experiences, not less.

Ego Death: Becoming One With the Medium of Mind

What I find is the earlier observation and remark that the brain, for a brief period, stops “existing.” I am alluding here to a widely studied phenomenon in the psychedelic literature referred to as ego death, or ego dissolution.

The experience of ego death consists of an altered state of consciousness in which there is a dramatic breakdown of one’s “sense of self.” Several neuroimaging studies have consistently demonstrated that psychedelics reliably facilitate this breakdown, something that occurs through the disintegration of an important brain network called the Default Mode Network (DMN) (see 2015, 2019 and 2020). The DMN is regarded by some neuroscientists to represent the neural correlates of the self or ego, as increased brain activation is primarily seen during self-referential processing.

Bernardo interprets the neuroimaging findings in the context of idealism by using the whirlpool metaphor: “I couldn’t help but visualize the deactivation of the ego functions as analogous to someone inserting one’s hand in a whirlpool, disrupting the ‘loopy’ flow that maintains it, and thereby allowing the water molecules originally trapped in it to escape.” Within this metaphor, the hand represents psychedelics that perturb the dynamics of the brain and how it dissolves the sense of self, or ego, through disintegration of the DMN.

We have read before that study participants report “geometrical patterns” and experiences of “dream-like quality.” What else do they report during a psychedelic peak experience? More importantly, what do they report when experiencing ego death, or ego dissolution, once their DMN disintegrates? Lots of anecdotal reports can be found from the Erowid experiences vault, but these might not be considered as reliable or valid. Fortunately, there also are findings from clinical trials.

One such study was conducted by the Imperial College London. This trial’s primary objective was to investigate if psilocybin was effective in helping people overcome their treatment-resistant depression. This consisted of a group of 12 people who were seriously depressed, some of which “have had a depression for an average of 18 years and tried between three and eleven antidepressant medications and up to six courses of talking therapy and none of which had helped them.” With a response rate of 67% (N = 8) only one week after treatment, and another 42% (N = 5) of individuals who remained in remission (symptom-free) after three months, the results of this study were extraordinary, particularly considering the tenacity of the participants’ depression and after receiving only two oral doses of psilocybin.

Six months later, the study participants were interviewed by one of the research team’s clinical psychologists Dr. Rosalind Watts. She asked them a series of questions to assess patient experiences during the psilocybin sessions, including the million dollar question: “What happened during dosing?” I refer the reader to the article itself or to watch Watts’ presentation to prevent you from becoming overflowed by tedious and superfluous amounts of awesome quotes. Down below I have listed some of the most revealing descriptions that seem to correspond with the whirlpool metaphor and idealism.

In an entire paragraph devoted to the ‘Connection of a spiritual principle’, Watts describes what happened during the psilocybin session. Here, patients frequently report “strong feelings of compassion, love, and bliss” that were often beautifully put, almost poetically. For instance, one of the participants stated that during the dose: “I was everybody, unity, one life with 6 billion faces, I was the one asking for love and giving love, I was swimming in the sea, and the sea was me.” This is a particularly clear example that corresponds with the metaphor of the whirlpool, as the participant literally mentions how she was swimming in the sea and realized being a part of it.

Another report hits the nail on his head by exemplifying this transition: “Before I enjoyed nature, now I feel part of it. Before I was looking at it as a thing, like TV or a painting. You’re part of it, there’s no separation or distinction, you are it” (italics added). Other participants reported similar experiences during the dose, such as “connecting to all other souls” or that it “felt like sunshine twinkling through leaves, I was nature” (italics added).

I was everybody, unity, one life with 6 billion faces, I was the one asking for love and giving love, I was swimming in the sea, and the sea was me

In general, the reports seem to follow a common narrative, namely that they are part of something greater than their little ‘selves’. Study participants as whirlpools have become one with the medium of the lake again. We can even be bold to suggest that these participants realized that they were “nothing to the whirlpool, but the lake itself.”

Analogously, the ego and the sense of self stops existing, as the DMN disintegrates and the contents of mind become one with the medium of mind. The great philosopher Alan Watts provides the quintessential description: “We do not ‘come into’ this world; we come out of it, as leaves from a tree. As the ocean ‘waves,’ the universe ‘peoples’. Every individual is an expression of the whole realm of nature, a unique action of the total universe” (italics added).

Future Musings and Grokking Idealism

As mentioned in the introduction, our view of the world determines in large part how we relate to ourselves, others, and the world. Now, if we maintain that the metaphysics of idealism is true – and we are indeed all whirlpools of the same lake – consider first how this will affect your life and how you will behave to your fellow human beings. Bringing hurt to someone else would then literally mean bringing hurt to oneself.

But I think the implications of idealism go much further than this. In fact, idealism made me think a lot about what Carl Sagan alluded to in his brilliant TV series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage: “a new consciousness is developing which sees the earth as a single organism and recognizes that an organism at war with itself is doomed.” And this is what idealism does – it recognizes that we are all, in Huxley’s words, potentially Mind at Large.

This has led me to ask two fundamental questions that hopefully can be answered in the near future. Might the metaphysical framework of idealism result in a significant reduction of unnecessary conflict and suffering in the world as it sees that we are all connected? And what important role do psychedelics play in facilitating this worldview?

The possible transition of materialism to idealism will probably take some time. In part, this is because it is extremely difficult to intuitively understand, or “grok”, idealism. This inability is exacerbated through our cultural milieu that always rejoices in the viewpoints of materialism: “we grew up to believe that mind is a product of the brain, not the other way around”, says Bernardo. As a result, it has been imprinted in our very way of being and can be considered as the lingua franca of contemporary metaphysics. It is the exact reason why Bernardo provides some solace to his readers through the advice of giving all this some thought to let the metaphysics of idealism sink in.

Indeed, the drastic change in worldview does not come naturally to us. It requires what is coined by renowned philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn a paradigm shift – a fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a certain discipline. What is more, we are protected by ourselves from what is referred to as an “ontological shock.” This happens particularly when beliefs are diametrically opposed to prior held personal, religious, or spiritual beliefs – something that OPEN director Joost Breeksema and neuroscientist Michiel van Elk refer to in Working with Weirdness.

Bringing it all together, I believe we are at the precipice of another Copernican revolution and that Bernardo represents a modern day version of Giordano Bruno. Bruno was a 16th century philosopher tried for heresy by the Roman Inquisition and subsequently burned at the stake for his cosmological theories (e.g., stars were distant suns surrounded by planets). Such ‘theories’ are now considered common knowledge, and more importantly, common sense. Only centuries later, Bruno has been characterized as a martyr for science. Might the same be said of Bernardo? Possibly so, as in his own words, “future philosophers will be merciless at our stupidity.” Let us not “burn” him at the stake, for Bernardo’s thoughts too can one day become common sense.

Dr. Bernardo Kastrup will give his presentation titled Psychedelic effects are one piece of a much bigger puzzle on Saturday September 24th at ICPR 2022 in the Philharmonie, Haarlem.

Bio

Bernardo Kastrup is the executive director of Essentia Foundation. His work has been leading the modern renaissance of metaphysical idealism, the notion that reality is essentially mental.

He has a PhD in philosophy (ontology and philosophy of mind) and another PhD in computer engineering (reconfigurable computing, artificial intelligence). As a scientist, Bernardo has worked for the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) and the Philips Research Laboratories (where the ‘Casimir Effect’ of Quantum Field Theory was discovered).

Formulated in detail in many academic papers and books, his ideas have been featured on Scientific American, the Institute of Art and Ideas, the Blog of the American Philosophical Association and Big Think, among others. Bernardo’s most recent book is Science Ideated: The fall of matter and the contours of the next mainstream scientific worldview. For more information, freely downloadable papers, videos, etc., please visit www.bernardokastrup.com.

Podcast appearances

Jaimungal, C. (Host). Bernardo Kastrup on Analytical Idealism, Materialism, The Self, and the Connectedness of You and I [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lAB21FAXCDE

Kieding, J. (Host). (2021, June 15). Bernardo Kastrup — The Man Behind the Ideas: Identity, Truth, Philosophy, and Psychotherapy [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jylqAohnzRY

Common misconceptions

There are several misconceptions about idealism (listed below). For this I refer the reader to pages 64 to 69 in Why Materialism is Baloney:

1. Idealism is not solipsism;

2. Idealism is not panpsychism;

3. Falling back into realist assumptions: “where is this mind stuff?”

4. Why can’t we influence reality at will if everything is in mind?