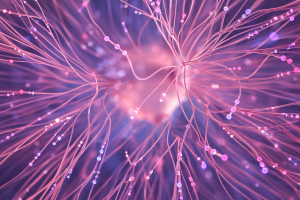

A Different Medicine, Postcolonial Healing in the Native American Church, Joseph D. Calabrese, Oxford University Press, 2013

This study is the result of two years of fieldwork with the Navajo in New Mexico. The author has both an anthropological and a clinical background, and combined one year of fieldwork with work in a clinic aimed at supporting young Native Americans with a drug and/or alcohol problem. This unique combination of anthropology and clinical psychology results in a ‘clinical ethnography’, in which the author analyses the use of peyote within the Native American Church. He examines, on the one hand, the place that peyote holds within the culture and the symbolism of the ritual, and on the other hand its use within a clinical treatment that supports young people in defeating their addiction with the help of rituals.

The first part of the book, about one third of the whole, is devoted to methodology and the theoretical underpinning that is necessary to observe the healing practices of cultures different from one’s own. For non-anthropologists this is quite enlightening, because it clearly shows the problems a researcher is confronted with when the cultural practices differ strongly from those he or she is used to. The most important subjects that are discussed in this part are the dangers of ethnocentrism and the necessity of self-reflection, but this discussion also provides some exciting ideas that stretch our understanding of therapy itself. The emphasis on how therapy is embedded in the culture and mythology of a group of people simultaneously raises the question whether and how this happens within our own culture.

Calabrese states that within Navajo culture (and many other traditional cultures that use psychoactive substances within their rituals) the concepts psychopharmacology and psychology do not exist and that the Navajo do not think in terms of these two different fields of science. The symbolism of the rituals is also connected to the broader cultural mythology, through which the healing process is embedded within a wider cultural narrative applicable to all members of this culture. In the West this so-called therapeutic ‘emplotment’ is often aimed at a scientific model of the psyche, or at a personal story that gives direction in the healing process.

By becoming aware of our cultural prejudices through a dialectic with other cultures, we can learn to better understand others and ourselves. Calabrese supports this idea by writing texts that engender empathy and thereby induce a better understanding of the other and therefore of ourselves. By focusing his research on the use of psychoactive substances within a healing ritual that is at the same time spiritual, Calabrese intends to demonstrate that current views on the use of such substances are in need of revision. Instead of focusing on who takes which substance, he pleads in favor of examining the way in which such substances are used within a broader cultural context, and asking the question whether or not this is useful or healing.

In the second part Calabrese further analyzes the symbolism in the rituals of the Native American Church. First he discusses the history of this church and the way in which it has been misunderstood time and again (as a heathen ritual or as an excuse for drug use). He goes on to successively elaborate the view on peyote held by members of the church, the nature of the ceremony and the role the church plays in socialization and the creation of community ties. Lastly, he describes the way in which ceremonies are embedded within Native American mental healthcare.

The members of the church see peyote both as a medicine and as a spirit. Some emphasize the medicinal aspect, others the spiritual aspects, so that no uniform understanding can be identified. Calabrese also notes the personal relation people have with peyote and thereby confirms that personal interpretations remain possible. These interpretations partly fit within the broader (not exclusively Native American Church affiliated) Navajo culture, and partly they are unique to this church.

The ceremony itself is aimed at healing, and the ritual supports this process by means of the various symbols that are central to it. By reflecting on these symbols, communicating with the medicine or the spirit of peyote, and through the transformative power of the experience, the members of the church see their own life in the light of the mythology of death and rebirth within which their healing becomes meaningful. The therapeutic process focuses less on the relation between therapist and patient and more on the personal relationship a person engages in with the medicine within the ritual context.

The members of the church also see the ceremonies as a form of socialization, where family ties and friendships are strengthened. Children are introduced at an early age if they show interest. There is a lot of resistance against this within Western/Christian culture, but Calabrese shows that after several decades of these practices it still hasn’t been proven that such use of peyote by young people within the context of the church has any negative consequences. Peyote is seen as a force that helps strengthen relations and stimulates one to live an ethical life. It also plays a role in the upbringing and development of young Navajo’s. For example, there are special ceremonies to support them in the challenges they face in their regular education, where the group prays for help and guidance.

The Native American Church ceremony has even earned a place in the officially approved treatment methods for young people that have a problematic drug use. This is in sharp contrast with the fact that peyote is officially scheduled as a substance without any medical application. Calabrese has observed in his work at the clinic how the ritual helped support young adults with such problems in their healing process, and simultaneously notes that, because of the official approval of the use of peyote, bureaucracy has shaped the ritual itself. For example, it is required to be aimed at the treatment of addiction in one or more young adults instead of a more general ritual as in the regular church services.

With this book, Calabrese argues for a cultural pluralism within mental healthcare. By connecting patients to rituals and practices from their own cultural backgrounds, a valuable aspect of their healing process is addressed. By participating in peyote ceremonies, young people with substance abuse problems are shown a valuable example of how to use substances in a way that is not destructive, and in many cases even healing. At the same time it reconnects them to their parents and family and restores the ties that have been broken. By acknowledging that there are different ways that can help within a healing process, Calabrese exposes the hegemonic cultural ethnocentrism and the ideological prejudices that often prevent us from thinking clearly about the traditional use of psychoactive substances in different cultures.

In summary this book is an excellent addition to the existing literature on the Native American Church, especially because it tries to acknowledge and circumvent existing cultural prejudices, in order to engender an analysis rooted in mutual respect. This is not only important for the use of a powerful psychedelic substance, but also to bring to light the negative impact of colonialism and to envision a world in which the pain that is still alive among Native Americans can be healed and overcome.

Buy this book on bookdepository.com and support the OPEN Foundation