’Psychedelic professors’ on the rise as universities expand courses on psychedelics

If you attended university or college and didn’t have an option to take a course on psychedelics – that was because they were practically nonexistent until very recently. Up to the beginning of this century, getting educated about psychedelics meant researching on your own, learning from elders, attending the few conferences that existed, reading available journal articles and books, or maybe joining secret psychedelic societies (in person or on the internet).

But today we are simultaneously experiencing a rise in international psychedelic research and an international acceptance of this field as a genuine, revived field of science. As a result, there is an emergence of university courses. And not just in a few places, but in some very prominent universities.

ㅤ

The psychedelic professors

The relative novelty of this educational endeavor spiked our interest: What are the types of courses offered? How are they organized and taught? What type of students are taking them? And what are the biggest challenges in teaching about psychedelics? We’ve interviewed three professors of current psychedelic courses at prominent research universities, who can rightfully call themselves psychedelic professors: Kim Kuypers (Maastricht, NL), Gianni Glick (Stanford University CA, USA), and Brian Pace (Ohio State University, OH)

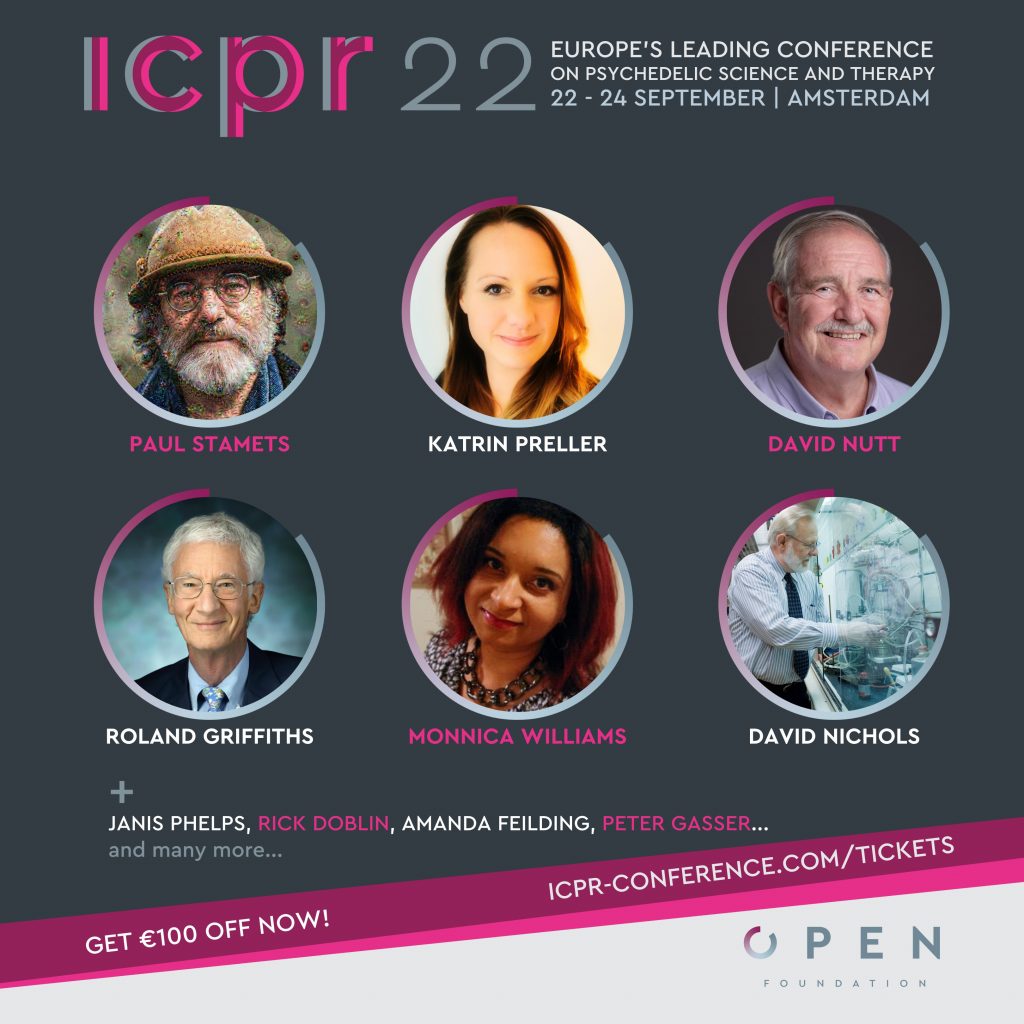

Kim Kuypers, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. Dr. Kuypers focuses on “Me We Biology”, trying to understand the biology of mental well-being. She researches psychedelics and their effects on cognition, creativity, hormones, and the mechanisms underlying these effects. Dr. Kuypers will be a speaker at this year’s ICPR conference.

Giancarlo “Gianni” Glick, MD, is a 3rd-year psychiatry resident at Stanford whose psychiatric focus is on the interdependence of emotional and physical well-being for his patients. He is also the organizer of the Stanford Psychedelic Science Group.

Brian Pace, PhD, is an affiliate scholar with the Centre for Psychedelic Drug Research and Education in the College of Social Work and a lecturer in the Department of Plant Pathology at The Ohio State University. Trained as an evolutionary ecologist, Brian studied agroecology, climate change, and ethnobotany. He is the Politics and Ecology Editor at the 501c3 psychedelic watchdog Psymposia and is currently a part of the team organizing Psychedemia, an interdisciplinary psychedelics conference scheduled for August of 2022 at Ohio State.

Here is what they teach, how they teach it, and why it is important they do it.

ㅤ

Q: Which courses on psychedelics do you teach?

A: Kuypers (Maastricht) “Psychedelic Medicine” is an 8-week long elective course for third-year bachelor’s students which is housed in Maastricht’s department of psychology. I also teach a first-year elective course in the same department, called “Drugs in the Brain”. This is for first-year students and is only 4 weeks long. This helps to serve as good preparation for those who will take the psychedelics class.

A: Glick (Stanford) “Introduction to Psychedelic Medicine” is a 10-week course, housed in the department of psychiatry at Stanford Medical School. This semester we have 187 students enrolled. It is an elective course and the make-up is about 70% undergraduates and the rest are graduates of all kinds. We also have many auditors ranging from neuroscience postdocs to attending psychiatrists. This makes for a huge range of expertise and familiarity with psychiatry.

A: Pace (Ohio State) “Psychedelic Studies: Neurobiology, Plants, Fungi, and Society” is a 14-week/one-semester course and it is through the Department of Plant Pathology. The course is for undergraduate bachelor’s students, without any prerequisites, but I frequently have graduate students as well. The majority are third and fourth-year students. There is also a new course being taught in our department called “Psychedelic Bioethics,” taught by my colleague, Dr. Neşe Devenot.

Q: What are the key learning outcomes for your students?

A: Kuypers (Maastricht) I want the students to know about the rich history of psychedelics and to be educated on both the positive and negative aspects of these substances. I place a major focus on how to properly read a scientific article: reviewing the research methodology, analyzing the results, and having a critical mind about it. I see this course as really the first way of getting the students acquainted with psychedelics and from here they should be able to navigate the future research that comes out with a better eye, and maybe also be inclined to get into the research and/or work in psychedelic-assisted therapies themselves.

A: Glick (Stanford) This question keeps me up at night, but I hope for a good cause – there are so many decisions about what to present, how to engage, what sequence of information makes the most sense. Ultimately, I want to prepare students to critically interact with everything they hear in the media and in the scientific literature about psychedelics. This course covers the foundational principles, history, and context for these students to then ask more questions and hopefully contribute to the field of psychedelics, themselves. I think one of the first questions we try to ask is: What does it even mean to call psychedelics medicines? And in doing so understand that we are applying a particular frame to it, specific to this pre-FDA-approval moment in time and space. While it’s nicer pedagogically to stay focused on psychedelics as a medicine, we also tell them that psychedelics can be many other things: sacraments, recreation, and so on. But for this course, we focus on them as medicines.

A: Pace (Ohio State) As the instructor of a course on psychedelics it is my job to prepare students to engage intellectually, become better communicators, and to have better conversations around a controversial topic that is rapidly taking center stage. Frankly, there are a lot of grifters in the psychedelic space, people who are attempting to own the space, and so part of my responsibility is to provide students with tools to critically evaluate psychedelic science and health claims, the job market they may enter, and to hopefully have these students make informed choices.

Q: What is the greatest challenge in teaching your course on psychedelics?

A: Kuypers (Maastricht) I haven’t had too many difficulties in teaching this material. I did have an incident where I was teaching about animal research that was done with MDMA to investigate neuronal death, and in doing these studies I discussed the methodology which included decapitation to further look at their brains. As a result of saying so I had a student who left the room because they could not bear to hear this type of work. Though not directly related to in-class learning itself, I have had emails sent to me from parents of children who have abused drugs who question whether I am being too positive about these compounds, even going so far as calling me the devil. But in the 4 years of teaching this course, I have not faced many challenges from students.

A: Glick (Stanford) Trying to figure out – what are the first principles of psychedelic medicine? Where do you start? How to strike a balance between asking big, zoomed-out, philosophical questions of human life and suffering (which I think is what this is really about), while staying in close contact with the data, the practice of medicine, counterpoints to my own views, and a sober take on all of this. How to teach students a kind of big picture schema that new ideas and facts and questions can fit into.

A: Pace (Ohio State) Psychedelics are inherently interdisciplinary. I’m not a psychiatrist. I’m not a social theorist. I’m not a political scientist. Yet these topics are as necessary to address as botanical, mycological, or neurochemical considerations–even though more broadly they may exceed the scope of my expertise. This can be challenging at times, but manageable. What is truly challenging is that issues like colonialism, addiction, and traumatic experiences are discussed in my course, and the reality is that some of the mental health distress faced globally is experienced personally by some of my students. Real injustice never gets easier to talk about, especially with those who are directly impacted by it.

ㅤ

One early psychedelic professor is Dr. Neşe Devenot – now an Affiliate Scholar at the Center for Psychedelic Drug Research and Education at Ohio State University.

She advocated for Psychedelic Studies courses for years, formally so in an essay in 2011 entitled “A Declaration of Psychedelic Studies”. Her first class, “Poetic Vision and the Psychedelic Experience,” ran from 2011 to 2012. A later class called Drug Wars had a focus on psychedelics and featured guest lectures from Matt Johnson and others working in the field. Her “Higher Dimensions in Literature” class in 2014 read McKenna and Castaneda. She went on to teach Psychedelic Studies at the University of Puget Sound from 2015 – 2018.

ㅤ

Q: What pedagogical tools do you use in your course?

A: Kuypers (Maastricht) For both the “Psychedelic Medicine” 8-week course and the 4-week “Drugs of the Mind” course I use Problem Based Learning (PBL). This pedagogy works by bringing real-world problems to the class which functions as vehicles for students to have to look up things they don’t know, synthesize an answer based on their research and these problems are generally guided, often providing one part of a problem at a time. An example of the last PBL assignment was a problem evaluating the positive and negative of the field of psychedelic medicine. In terms of course materials, I developed a course manual and we also use recent research articles for the “Psychedelic Medicine” course. In the 1st year course “Drugs of the Mind” course we use David Nutt’s “Drugs Without the Hot Air”. I do most of the lectures but some of my colleagues help as well. We have a limited amount of time in these courses so we provide additional resources online for students to read and watch on their own.

A: Glick (Stanford) Two years ago the course started as a lecture series, with a different speaker each week presenting on their area of expertise. We updated the second iteration (last year) to have a more coherent through-line and progression of topics, with added small group discussion. And this year we tried to improve that further, so we spent the first third laying the foundational principles, the second third hearing from serious experts in the field (Brian Anderson, Jennifer Mitchell, Robin Carhart-Harris), and the final third weaving everything together. The best session is always the last one when students give 5-minute presentations to the class on any topics or psychedelics subgenres they found interesting. This year they taught us about psychedelics in China, the Eleusinian mysteries, research in psychotic disorders, and a bunch more.

A: Pace (Ohio State) This is a lecture-based course accompanied by reading articles and watching videos that conclude with 30-minute discussions each class. Since it is a course goal is to get students to have better, evidence-based conversations around psychedelics, students write weekly reading reflections showing that they are considering the material and reflecting on how they feel, and how these topics may connect to their life. Students also do presentations which are evaluated in part by peer review. From day one I am walking students through difficult, yet respectful conversations; you can’t understand psychedelics without touching on topics like consciousness, perception, religious experiences, and criminalization.

Q: What do you believe is the ROLE of university courses in the psychedelic renaissance?

A: Kuypers (Maastricht) It is incredibly important to have these available. I get requests from therapists and psychiatrists who did not get these types of courses in the curriculum of their educational training. Some of them also tell me of the cost for psychedelic-assisted therapy training from private institutions that can cost upwards of 20,000-25,000 Euros, which is crazy. Instead, this type of education should be embedded within all levels of university education from bachelor’s, graduate, and medical education. We definitely need psychedelic-assisted training for therapists in the universities (instead of the private organizations).

A: Glick (Stanford) Similarly to how Johns Hopkins, NYU, and UCLA have stewarded the research through this kind of rigorous academic environment, there is this similar way that universities may offer a credible education, with a kind of peer review process, with a set of checks and balances where you can’t just teach anything. Secondly, doctors should know about this. For medical students and psychiatry residents to be competent about medicines their patients are in some cases already using and that may soon become legal, this should be part of the curriculum.

A: Pace (Ohio State) Psychedelics were abandoned by institutions following the Controlled Substances act in 1970. The new-agey, cultish stuff we see around psychedelics now, with tuning your chakras and merging souls or whatever: that is our fault. That’s an abdication of the responsibility to investigate interesting questions and to chase down data: to find out how things work. So where we are now is a very timid and late re-entry to the subject, more so for education than research. Psychedelic research didn’t end when the universities and governments abandoned it. It continued in the underground. The role of the university courses on psychedelics is to identify and evaluate high-quality information on the topic. We have a lot of catching up to do and I think that should be done with humility.

Addendum: The author of this article, Dr. Joey Lichter, is a volunteer for OPEN and ICPR, but also a chemistry professor who teaches a course titled “The Psychedelic Renaissance” at Florida International University in Miami, FL USA, thereby also qualifying as another psychedelic professor.

’Psychedelic professors’ on the rise as universities expand courses on psychedelics Read More »