From the Field: Lessons from psychedelic practices in the Netherlands is a blog series based on my qualitative research at the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen in collaboration with the OPEN Foundation. The study focused on the conception and practice of safe and beneficial use of psychedelics in group settings in the Netherlands: more specifically in counterculture, ayahuasca ceremonies and truffle retreat centers. Based on in-depth interviews with experienced practitioners, the series highlights and connects diverse aspects of psychedelic practices, from cultural influences through ethics to sensory stimuli. This post dives deep into the role of music.

Part 1: Lessons on Psychedelic Harm Reduction with PsyCare NL – From the field

Part 2: Dutch Psychedelic Practices Shaped by Culture and Law

Part 3: From the Field: Music in Psychedelic Practices (current post)

Part 4: From the Field: Psychedelics and Nature

Part 5: From the Field: Psychedelics and Autonomy

Part 6: Safe and beneficial experiences

the heartbeat of a psychedelic experience?

Considering its centrality in human culture, it was not surprising that music came up as part of all the psychedelic practices that I (AA) studied, and was discussed in all interviews. As Izen et al explain, music “plays a unique role in human emotional, social, and cultural experiences”. It works “both in the moment and through the ongoing construction of our personal and collective social narratives.” It is subjective and personal, used for interpersonal communication, and part of societies’ cultural heritage.

Academically, music is studied not only for its harmonies, rhythms and the like, but also for its psychological merits, linguistic applications, mathematical forms, social aspects and of course, creative, artistic, and cultural values. According to The Origins of Music, research into music evolution could shed light on “emotional and behavioural manipulation through sound; interpersonal bonding and synchronization mechanisms; creativity and aesthetic expression; [and] the human affinity for the spiritual and the mystical” – among others.

There are manifold interactions between music and psychedelics in group practices. I suggest that the key to understanding them lies in the centrality and significance of music in culture, together with common and complementary qualities of music and psychedelics. Thus, this article will begin by shortly presenting some of music’s powers before reviewing its applications and meanings in psychedelic practices.

The Powers of Music: Orchestrating Emotions

When I was young, I composed a ‘crying playlist’. Whenever I needed a cry, I would just hit play… It worked like a charm, time and time again. This great emotional power of music is utilized in art forms like theatre and film, as well as for commercial purposes, in advertising and shops. Film score composers use music to enhance imagery, but also to generate feelings which are not related to what we see. For example, the soundtrack of suspense and horror films often makes us nervous and agitated even when nothing happens on screen, perhaps just a character walking from one room to another. As the video below demonstrates, music can easily manipulate our interpretation and lead us to contradicting conclusions about the same imagery.

Is music worth more than a thousand pictures?

The Powers of Music: A Bridge to Transcendence

Spiritual drumming, Tuvan throat-singing, gospel music, the use of gongs, repetition of mantras and the vocalization of the single syllable Aum are just a few examples linking sound to the transcendent. Alan Watts compared music and ritual to meditation, as non-verbal and thus non-conceptual perceptions of reality. “It brings us into a state of awareness in which the notions of self and other, past and future, knower and the known, mind and body, feeler and feeling, thinker and thought have simply disappeared.” Similarly, Stanislav Grof describes how unitive experiences can be triggered in both artist and audience, through the awe invoked by extraordinary artistic creations.

Besides eliminating time altogether, a musical piece can take you back to a specific moment in time and space. Sometimes, all it takes are a few notes. And while that moment is often from your personal biography, it does not have to be. Musical associations are also made through cultural productions, such as holiday and memorial days, films, television and so on.

Music and psychedelics

Music and psychedelics seem to have some things in common. On their own, they are emotional amplifiers; taken together, they enhance and influence each other’s effects. They can also complement each other: music’s ability to convey information without the need for words can be handy for ineffable psychedelic states. Influencing both set and setting, music gives a certain tone or atmosphere to the space; and depending on your taste and associations, it can change your mood, enhance existing feelings or stir new ones. Their associative power offers advantages and challenges alike. In a therapeutic context, research has shown music to contribute to significant therapeutic effects, but also to generate ‘negative’ or ‘unwelcome’ reactions.

In psychedelic therapy and in ceremonial settings, visual imagery is often treated as distracting, unwanted or too outward-bound. Guides suggest that participants use an eye mask or close their eyes. In the absence of imagery’s limits on plausible interpretation, sound can take the lead. Participants may feel they are walking inside the music, as if it were a scenery. They may experience auditory hallucinations, synaesthesia, or a lack of separation between themselves (the perceiver) and the music (the thing perceived), sometimes referred to as ‘ego death’. The multidisciplinary scholar Gregory Bateson calls this a state of “correct thought”, because while sound is a thing-in-itself, our perception of it is a part of mind. And while some (like himself) may require psychedelics to achieve this state, he is of the opinion that artists have always known it. To demonstrate it, he quotes Bach’s answer to the question how he played so divinely: “I play the notes, in order, as they are written. It is God who makes the music.”

My analysis showed there were few musical similarities in terms of content between the practitioners. However, the context of music use was quite similar. As we shall see, differences in musical choices can be explained as different views on the psychedelic process. To understand their common contexts, we will examine the use of music through cultural lenses, focusing on tradition and novelty between events and generations, and on collective active participation.

Music in Ceremony: Between Grounding and Transcendence

Most facilitators stated that they avoid lyrics altogether, or at least lyrics in languages that participants understand. Other than that, music in psychedelic practices is diverse and has numerous, sometimes contradicting purposes. For example, it plays a role in both grounding and transcendence. The types of music varied greatly between practices and facilitators. Albert plays only live music in his shamanic ceremonies, mostly with traditional instruments, and sometimes singing. In other ceremonies, recorded music is played solely, or in addition to live music, and can include original compositions, well-known pieces and multiple genres. Some institutions have curated music, but the music in each ceremony always depends on the facilitator(s) present.

Interviewees indicated that the person who leads the ceremony also determines the flow of the music, and thus holds great power and responsibility. Interestingly, all of them spoke about music in intuitive terms, changing according to the needs of the specific group at specific times. As Ronald explained: “It’s always like tuning into the space, what the space needs most…; if it needs a little… push over the edge so to speak, or if it needs a lot of calming and grounding.” Expressions such as “tune into the space” and “feel the energy” were repeated across interviews, whether or not speakers had a musical background. The responsibility associated with delivering the right music at the right time was also widely acknowledged, with Ronald even linking his musical experience to him being qualified to work as a guide.

According to all respondents who organise ceremonies, be it with ayahuasca or truffles, music is used in different ways during preparation, at the height of the psychedelic experience and for integration. One of its roles, as explained by some interviewees, is to serve as an anchor for participants, a safe place to go back to or hold on to when the experience becomes too intense. Thus, intermittent moments of silence create space for diving deeper into the experience, and the music allows participants to resurface again.

During the peak of the experience, music is at its strongest and can create dramatic effects. Practitioners choose the type and emotional intensity of their music, when and how to use it. According to Mendel Kaelen, music is always directive, i.e. guiding participants’ experience, an opinion that several facilitators seem to share. For some, this is an opportunity, for others a warning sign. Thus, Anton describes the peak stage as when they “go quite deep, sometimes really dark, or a lot of piano music”; Anna tries to avoid piano and violin in order to “be in service of the processes that are already there.” Practitioners’ musical choices seem to reflect different approaches to the psychedelic process itself, which in turn create diverse styles of ceremonies.

At the end of the ceremony, some practitioners play more upbeat or contemporary music, using its associative character as a means for bringing people back to a normal waking state. Multiple facilitators write down or record the music played during a ceremony, and share it later with participants, in order to reconnect with the experience as part of integration. Playing only live, recordings help Albert in preserving musical novelty which happens during ceremony and is difficult to retrieve later.

Music in Counterculture: Lead Your Own Journey

In (counter)culture, events often revolve around the music, and its scope depends on the type and size of the event. Representatives of the studied cultural institution organize multifaceted productions, where music is often the heart of the event or one among other artistic disciplines. Here too, both live and recorded music can be found in parties, concerts, festivals, performances and theatrical shows.

Typically, the bigger the event, the more musical variety. Smaller events have a certain character, creating a particular setting. One example which came up in an interview was an annual Celtic spring celebration. In this light, flowery event, mostly acoustic music is played, and “because it’s so full of ceremony, I think a lot of people enjoy a psychedelic twist to it”. In parallel, all-night psychedelic trance parties are hosted a few times a year, with loud music and light effects. “Everybody has their own preference.” The vibe and line-up of a future event set expectations, and participants can choose the music suitable for their psychedelic experience. Larger festivals host multiple stages, playing various musical genres close to 24 hours per day. Here, a diverse lineup is made by the facilitators, and the participants navigate through a landscape of musical spaces.

Familiarity and Novelty, Structure and Variation

Discussing familiarity and novelty of music, Kaelan explains how unfamiliar dimensions of music can evoke distinct individual reactions of alienation, analysis and transcendence. Novelty can inspire both discovery and fear, and familiarity can “hold the experience together within a sense of support, belonging and care.” This is indeed reflected in the use of music in ceremonies, as we have seen.

Now, instead of looking at individual therapeutic benefits, let us replace our lens for a cultural one, where music is first and foremost an art form. Group practices allow a glimpse at how music and psychedelics interact in relation to cultural heritage and change. Ceremony facilitators indicated a combination of repetitiveness and novelty. Recurring elements, such as an opening song, create a structure filled by music which is played more spontaneously.

Albert adheres to a specific cultural tradition. Together with his permanent partner, they play the harmonica for its importance in the Colombian-Amazonian tradition, alongside traditional instruments, such as the maraca, bandola, Jew’s harp and several flutes, drums and handpans. Like in other shamanic traditions, the music is not conceived as an addition to the psychedelic process, but as stemming from it. As Albert explained, he does not know what he is about to do when picking up an instrument, “the idea is that the plants guide us [in] making the music”. Singing is dependent on the appearance of related animals during the psychedelic experience, and has personal characteristics. So, for example, he can sing his condor song only if he sees the condor. After long years of collaboration, he and his partner play together as “a two-man orchestra”. Still, each ceremony can bring musical novelty as a consequence of the psychedelic experience and intuitive playing, producing slightly different results each time.

In other types of ceremonies, teams are sometimes larger, consisting of many musicians, with only a few present in each ceremony. Thus, the music played each time depends on who these musicians are, what they bring in musically, and on the interaction between them. Retreats and therapeutically-oriented ceremonies in the study play musical genres from different parts of the world, and sometimes their own compositions. Genres and styles varied from classical music and film scores to mantra songs, South American tunes and some traditional instruments like the duduk. However, not everything goes in the mix, and cultural sensibilities are applied. For example, songs from the Yawanawá and other indigenous communities were explicitly mentioned as not being played in a truffle retreat, due to their relation to ayahuasca. Anna does not play icaros in her therapeutically oriented ayahuasca ceremonies because they should be sung by a shaman.

Tradition and Change: Passing the Baton to the Next Generation

Zooming out of the here and now, the study brought some hints as to longer processes of change, between generations of facilitators. According to the Colombian tradition Albert was initiated in, “you’re not allowed to sing the songs of your teacher, you can only sing your own songs.” This older tradition includes an inherent mechanism for its own change. There is always some novelty, and shamans bring their own flavour to their ceremonies.

Approaching 80 years of age, Cor, a prominent figure in the Dutch counterculture, told me a story displaying the movement of music through cultures and generations in the artistic space. It all started in the coastal state of Goa, India, where trance music, or more specifically Goa trance were born. Before that happened, Goa was home to a hippie community of local and international musicians playing live together. “But then Dr. Bobby came from Detroit with the first batch of techno. And then at the same time MDMA was introduced in these parties… And it exploded into airplanes full of tourists coming to the raves. But what happened at the same time was that the culture, the live music, the contact between different people changed completely. Because now there was police and permits and promoters… So in my opinion Goa was kind of spoiled after that.” To his surprise, when Goa trance arrived in the Netherlands, it did so as a very progressive kind of music. The younger generation embraced it and did not approve of his protest: “come on, now you’re like your father. When you were playing rock ‘n roll, he knocked on your door, ‘stop that noise!’ And now you are doing it.”

Conflict around music was present in therapeutic ceremony practices as well, for two facilitators who are not musicians. Anna faced occasional yet ongoing criticism from other ceremony leaders, for not playing live music during ceremonies. Anton was approached by musicians in his own team about his directive style soon after replacing the former ceremony leader. Both personal and collective, the complexities of music demand facilitators of all practices to be sensitive on multiple levels, from global cultural sensibilities to differences between groups and individuals.

Active Participation: Communal Singing and Dancing

Active participation, in the form of collective singing, dancing and music-making, is a unique aspect of group practices. In addition to facilitating the mind-body connection within an individual, performed collectively, music and dance strengthen the individual-community bond. According to Bessel van der Kolk, they aid in trauma relief as they create a bond beyond one’s individual fate, and instill hope and courage. Indeed, he notes, collective humming, singing and movement, like rhythmic prayer, are part of religious rituals universally.

In some of the studied ayahuasca practices, collective singing is a regular part of the ceremony. Anton explains: “especially in the opening, we have collective singing, we call it the serving hymn”; other hymns follow at a later stage. As hymns are repetitive in nature, newcomers can join in singing quite easily, encouraged and helped by the musicians and more experienced participants. In Albert’s shamanic ceremony, there is room for participants to join in music-making at a specific time.

Dance was mentioned as part of most practices, often in the context of preparation for ceremony. In counterculture, communal dancing is the raison d’être of some events, such as parties. Often associated with clubs and taken for a contemporary practice, collective dancing is not a new thing. Ecstatic dance is an ancient old consciousness-altering technique which has its spiritual roots in traditions around the globe. Participants may reach an altered state of trance or ecstasy through music and dance, and may or may not choose to consume psychedelics in addition. At any rate, music and (collective) dance are not there just to accompany a psychedelic experience, but for their own intrinsic value. A study into the use of psychedelics in music festivals showed it to have a positive effect on people’s lives and wellbeing. It was contributed partially to the setting, where “art generally and music specifically were found to be ‘the guide’ or ‘the container’ for the experience”.

Considering the complexity of both music and psychedelics, the relations between them seem to be almost unfathomable. Ronald wondered if perhaps all music talks about the same things, about the human experience, or what it means to be human. Music allows us to reach deep into ourselves, connect with others or discover a whole culture. Combined with psychedelics, maybe these distinct features are revealed as one and the same thing.

Interviewees aliases table

| Type of practice | Interviewee alias | Additional info |

| Ayahuasca ceremonies | Albert | Colombian tradition initiated shaman |

| Ayahuasca ceremonies | Anna | Therapist |

| Ayahuasca ceremonies | Anton | Creative and integrative facilitation |

| Counterculture | Carla | Cultural organization chairperson |

| Counterculture | Chris | In charge of cultural activities |

| Counterculture | Cor | Community/institution co-founder |

| Retreat centre | Rob | Microdosing coach |

| Retreat centre | Ronald | Musician, individual coach |

*******

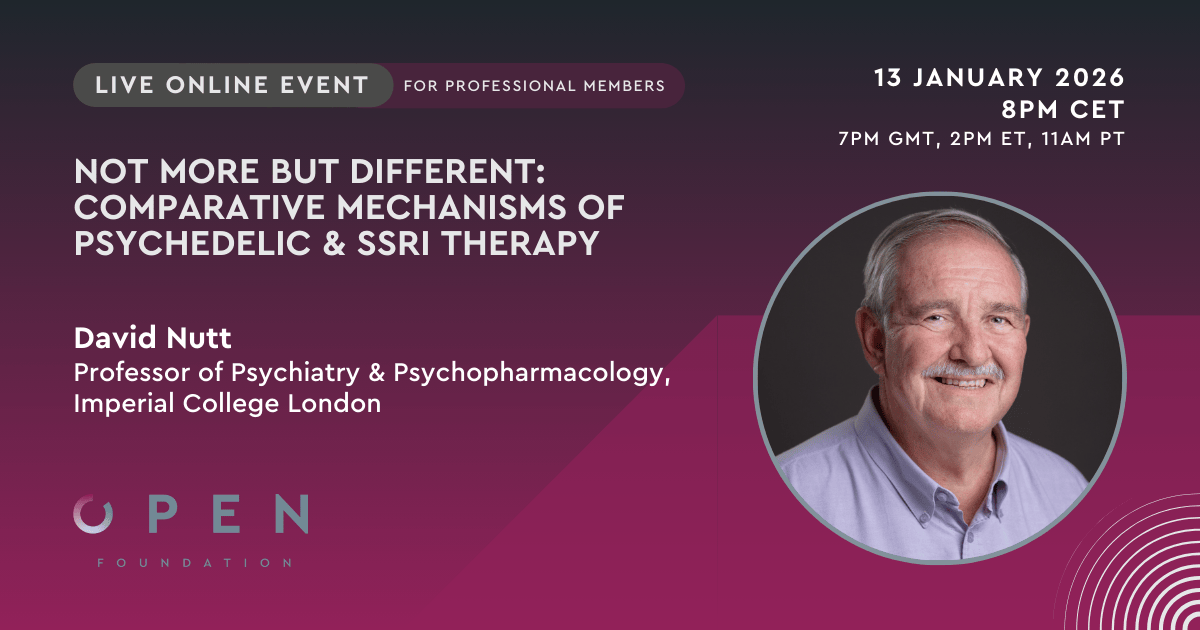

Psychedelics & Music Series – OPEN Foundation

In the coming months, OPEN will host a series of online events around music and psychedelics, bringing together leading musicians, shamans, researchers, and clinicians. Together, we’ll delve into the history of music in psychedelic contexts, its role in indigenous practices, emerging research in clinical settings, and the art and ethics of creating soundscapes for altered states.

The series launches on January 22 with a panel on Crafting Music for Altered States and Psychedelic Spaces. Featuring Krishna-Trevor Oswalt (East Forest), Xóchitl Kusikuy Ashe, and Andrea Drury (ANILAH), and moderated by Liz Hanna, this discussion will explore their creative processes, how they integrate intention with craft, and the unique philosophies guiding their work in ceremonies and therapeutic settings.

Stay tuned on LinkedIn, Instagram or via our newsletter below

Agenda

February 13: The History & Evolution of Music & Psychedelics with Katarina Jerotic

February (TBD): The Role of Music in Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy, a panel discussion with Fred Barrett, Catharina Messell, and Mendel Kaelen (exclusive to professional members)

April (TBD): Deep Listening Session and Q&A with Mendel Kaelen (in-person event)

May 14: Icaros and Music in Entheogenic Traditions with Susana Bustos