On March 19 and 20, 2023, the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) organised the New Frontiers Meeting on Psychedelics in Nice, France. Various researchers and clinicians joined this event to talk about the current state of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (PAT). Here are some of the most interesting developments in the field of psychedelic research.

The ECNP New Frontiers Meeting: Psychedelics 2023 was kicked off by Gitte Moos Knudsen, the current Chair and president of the ENCP and professor of the neurology department at the Rigshospitalet and University of Copenhagen, Denmark. She laid out the program of the conference that consisted of three sub-topics, including pharmacology, clinical aspects, and clinical trials. Furthermore, Knudsen presented the Gartner Hype Cycle to the audience and asked whether there is a current hype in psychedelic research and where we might be in this Hype Cycle. Virtually everyone raised their hands which made it clear there is indeed a hype in the psychedelic field.

Knudsen’s introduction was followed up by Professor David Nutt from Imperial College London who gave an overview of the current state of psychedelics. In brief, he mentioned how psychedelics seem to show efficacy in depression and addiction and shared some of the therapeutic mechanisms of action in the brain, such as alterations in brain connectivity, reduced modularity, and increased neuroplasticity.

Most notably, Nutt shared one of the most recent brain imaging findings of N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) that were yet to be published. According to Nutt, this work is probably the “most impressive study ever done at our department” as it contains the most comprehensive view of the acute brain action of psychedelics to date. This was made possible through the use of both electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to record brain activity before, during, and after the ingestion of intravenous DMT and comparing it to placebo in twenty healthy individuals. In general, the results of the now published study demonstrate that DMT is able to induce network disintegration and desegregation, decreases in alpha power, increases in entropy, altered traveling waves, and global functional connectivity. In other words, a lot is happening during the DMT-experience, and this naturally reflects the peculiar and extraordinary experiences that individuals generally report.

In the evening of March 20th, directly after the ECNP conference, the results of the study were published in The Guardian reporting how the recordings of DMT reveal a “profound impact across the brain.” One can safely say that this is a clear testament of the hype of psychedelic research and how the media wants to pick up on this latest news.

Nutt further showed yet to be published results from another neuroimaging study that is based on the well-known psilocybin versus escitalopram trial. The team already demonstrated psilocybin-specific effects in the brain last year, such as increases in global integration and decreases in modularity. And now they found more differences between the two substances, namely that escitalopram resulted in a blunted response towards emotional faces. This finding was not demonstrated in the psilocybin condition of the study and further adds to the view that antidepressants seem to blunt people’s emotions.

Finally, Nutt notified the audience of some future policy decisions. This included the statement that US president Biden will make psilocybin and MDMA legal in the next two years and that Australia will reschedule both substances by July 2023.

Animal research: psychoplastogens and affective bias tests

Another prominent subject that has recently entered the field of psychedelic research is the therapeutic use of so-called psychoplastogens. Psychoplastogens refer to a class of substances that are able to rapidly promote neuroplasticity without any hallucinogenic effects. This presentation was given by David Olsen, an associate professor of chemistry, biochemistry and molecular medicine at the University of California, Davis. Olsen is also the co-founder and Chief Innovation Officer of Delix Therapeutics, a company that focuses on the development of psychoplastogens.

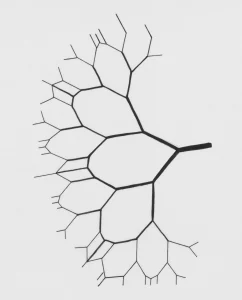

As mentioned briefly, psychoplastogens are aimed rapidly promoting neuroplasticity. Olsen mentioned during his presentation that this happens through “transforming the structure of the neuron.” Psychoplastogens establish this transformation in particular through “targeting dendritic spine density and increasing both their growth and complexity.” According to Olsen, a lot of neuropsychiatric disorders are due to a lack of dendritic spine density, hence the recent development of psychoplastogens.

One of the primary psychoplastogen candidates under development is tabernanthalog. This is a novel compound that is structurally similar to the psychedelic drug ibogaine. One study published in Nature in 2020 demonstrated that tabernanthalog was found to promote structural neural plasticity, reduce alcohol- and heroin-seeking behaviour, and produce antidepressant-like effects in rodents. What seems to be very promising is that all this was accomplished without any of the hallucinogenic effects generally observed following the use of ibogaine. Another more recent study found that only a single dose of tabernanthalog was able to promote the regrowth of neuronal connections and restoring functional neural circuits in the brain disrupted by unpredictable stress. This increase in neuroplasticity was accompanied by a correction in behavioural deficits, including anxiety and inflexibility.

But how did the researchers know that the rodents were actually not hallucinating? This was established by using the so-called head-twitch response, which is suggested to be a rodent behavioural proxy for hallucinations induced by 5-HT2A agonists. But I always wondered: How do we really know? Is the head-twitch response truly representative of hallucinogenic effects? Not surprisingly, one of the audience members asked during a discussion session what actually occurs in rodents during the head-twitch response. As it turns out, when you compare rodents who received 5-MeO-DMT to those who receive tabernanthalog, the former will show a robust head-twitch response, whereas the latter will not.

The discussion continued during dinner on day one with some other attendees and someone hypothesized that rodents not only see through their eyes, but through their whiskers. This sounded very fascinating and, as it turns out, the whiskers of rodents consist of sensory nerves that connect to well-defined structures in the cortex. Indeed, much like humans that use their fingers to navigate the world around, rodents use their whiskers to map out their surroundings and in turn build a 3D picture of the world.

Nevertheless, there are still many difficulties in translating subjective measures from humans to animals, particularly when doing research on depression-like behaviour. This was particularly signified by speaker Emma Robinson, professor of psychopharmacology at the University of Bristol. Nex to the head-twitch response, Robinson presented many other animal testing paradigms, particularly the sucrose preference test, forced swim test, and the novelty seeking test, which are used to assess depression-like behaviour in rodents. She stated that the use of any of these paradigms is suspect to lots of false-positives or false-negatives.

Because of the problems with current animal assays, Robinson and her team used the affective bias test (ABT) as it is suggested to have a better translational validity to humans. Within this assay, animals are trained for a week and have to learn to choose between two options (one positive, one negative) that will in turn reflect a positive or negative bias. It was developed to investigate the hypothesis that the cognitive processes associated with reward-related learning and memory may be modified by affective states. Robinson further explained that this is based on Aaron Beck’s cognitive triad model of depression, a cognitive framework that is often used to account for the negative views and dysfunctional thoughts observed in depression. The research that she presented is not yet published but revealed that one dose of psilocybin or ketamine is able to “completely attenuate the negative bias in rodents.” Translated to humans, this indicates that either psilocybin or ketamine might be able to help individuals with depression mitigate their dysfunctional and negative thoughts. But most importantly, it provides a therapeutic window and opportunity to develop a more realistic view about oneself, the world, and the future.

Drug-Drug Interactions to Increase Therapeutic Efficacy and Improve Harm Reduction

Robinson was followed up by professor of clinical pharmacology and internal medicine, Matthias Liechti, from the University of Basel in Switzerland. Liechti’s presentation was particularly mind-opening to me as he discussed some of the drug-drug interaction effects between psychedelics and other substances. For instance, when individuals with depression receive pre-treatment with the antidepressant escitalopram and then take psilocybin, there were less signs of anxiety and adverse cardiovascular effects. The most striking finding was that this interaction did not alter the psychedelic effects following the ingestion of psilocybin at all. Although this study was quite small with 27 participants and the daily pre-treatment of escitalopram only consisted of 7 days, this finding can be a huge implication for harm reduction in the field of psychedelic research.

Something else that Liechti presented came from an older study that was published in 2015. This study demonstrated that the co-administration of bupropion significantly increased plasma MDMA concentrations and, as a result, prolonged the positive mood effects of MDMA. But maybe even more important, this is another drug-drug interaction that can be used to improve harm reduction during a dosing session due to bupropion’s ability to significantly reduce the heart rate response to MDMA. Together, this indicates that using MDMA with bupropion can enhance mood effects while also lower cardiac stimulation.

Another drug that was mentioned during Liechti’ presentation was ketanserin. Ketanserin has been used in the past to demonstrate that psychedelics primarily target the 5-HT2A receptor. Indeed, when this drug is taken prior to LSD, ketanserin is able to completely attenuate the subjective effects. But a recent study has now also demonstrated its use for the reversal of the acute response to LSD. Specifically, ketanserin was able to significantly reduce the duration of LSD’s subjective effects from 8.5 hours to 3.5 hours and was able to reduce adverse cardiovascular effects. As such, ketanserin can be “effectively used as a planned or rescue option to shorten and attenuate the LSD experience in humans in research and LSD-assisted therapy.”

The Neurobiology of Psychedelics and Inter-Individual Heterogeneity

The second day was opened by Katrin Preller, a junior Group Leader at the University of Zurich, and a visiting Assistant Professor at Yale University. She talked about numerous subjects, including the neurobiology of psychedelics, the acute modulation of brain connectivity through psychedelics, and the four current network-level models of psychedelic action (for a full explanation of these models, please continue reading here).

Preller pointed out during her talk that virtually everything we know so far about psychedelics and their effects on the brain is based on averages of a group. This is why she asked the audience “what about inter-individual heterogeneity?” In other words, what about the differences between individuals when we compare them before, during, or after the psychedelic experience? Indeed, not everyone’s brain is exactly the same at the start of a clinical trial and it is something we should consider when evaluating the therapeutic effects of psychedelics. This conundrum led Preller to hypothesize the following, namely that “baseline connectivity is predictive of the acute effects and determines how someone responds to a psychedelic.” This hypothesis is explored further in upcoming papers that are yet to be published.

As a clinical neuropsychologist and someone who conducts neuroimaging research myself, I became very interested in this hypothesis and approached Preller during one of the coffee breaks to ask her how this brain connectivity would look like. She was not able to answer this question in detail because as the research stands, it has not been explored in full yet. I continued to ask whether such connectivity could be used as a marker to determine the dosage of a psychedelic or maybe even the type of therapeutic framework. We know, for example, that high connectivity in the Default Mode Network is associated with a high degree of rumination – one of the salient and important features of in major depressive disorder. Maybe this could in turn indicate the dosage amount and possibly even determine the choice of a specific therapeutic framework, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy targeted at increasing psychological flexibility. She partly agreed and reflected that it is particularly important to get a better understanding of the synergistic effects of both psychedelics and therapy that in turn optimize therapeutic outcome. But how brain connectivity can be used for this remains to be explored because we simply need more studies. Similar to how she concluded her presentation, we need to learn more about the brain so we can optimize PAT and prevent cost and frustration with patients.

The Design of Clinical Trials: a European Regulatory Perspective and Music

Nearing the end of the conference we were informed about the challenges regarding the design of clinical trials by Gerhard Gründer, Professor of Psychiatry and Chair of Department of Molecular Neuroimaging at Central Institute of Mental Health, Mannheim. As the research stands today, we have small sample sizes to fails to account for sufficient statistical power, there is a lack of control and difficulty with blinding, and an expectation bias with nocebo effects. These challenges are troublesome, but can be overcome when we conduct more research. Gründer also shared some e-mail messages from participants in order to show that the therapeutic alliance is the most important factor for efficacy and that we should take this into account when conducting trials.

To help establish the rigorousness of clinical trials with psychedelics, ECNP invited speaker Marion Haberkamp, a current core member of the CNS Working Party (CNSWP) at the European Medicines Agency (EMA), Amsterdam, and a long-time member and now expert of the Scientific Advice Working Party (SAWP). When it comes to psychedelic research, Haberkamp told the audience that “the findings are both intriguing and sobering” but that “we need longer and more trials.” Accordingly, Haberkamp talked about European regulatory guidelines and challenges that were recently published in the Lancet. As the age-old adage goes in academia, the authors of this paper posit that more rigorous research is needed, but not without giving any specific recommendations. For instance, they added that it is important to reconsider double blinding in clinical trials and the roles of both positive and negative expectancy created during preparatory sessions. Other points include the need to compare psychedelics with psychotherapy, further establish the safety profile of psychedelics, and continue to assess potential drug-drug interactions.

To realise all this, Haberkamp told the audience that there is direct help from the European regulatory office. For instance, researchers are able to come to the SAWP for qualification procedures. Moreover, there are already EMA guidelines for setting up clinical trials for major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, and anxiety. Haberkamp also announced that such guidelines will be available for psychedelics by the summer of 2023.

Patient Perspectives

I want to finale bring attention to Tadeusz Hawrot from PAREA (Psychedelics Access and Research European Alliance). Hawrot is doing a tremendous job in bringing attention to patients’ perspectives, because according to him it is “the patients who are the experts and the most we can learn from.” And this message particularly hit home through the testimony of Dave Pounds, a 59-year-old patient who has been suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for almost his entire life. A short summary of his story is described down below.

Dave explained to the audience that when he was just a young little boy, he witnessed his mother being raped and murdered at their home. This horrific experience led to the development of recurrent panic attacks in his teenage years and Dave was ultimately diagnosed with PTSD. He tried several types of treatment and an exorbitant amount of different drugs in order to get better, but nothing seemed to work. Even worse, the drugs only seemed to blunt his feelings. A few years ago, he discovered the work of Ben Sessa while Googling on the internet and read about the benefits of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. He decided to try it out and told the audience about his 1st experience with MDMA. Dave mentioned first of all how this was all very lucid and completely sober. While on MDMA, he returned to his own bedroom at 12 years old, frozen with fear, knowing what had just happened downstairs. The perpetrator came to his room upstairs, but whilst under the influence of MDMA he was not frightened anymore. His mom was also present in the bedroom, while Dave talked to the perpetrator about how he is going to be punished for what he has done. The most striking part of this story is how his mom turned to the perpetrator, hugged him, and wished him well. This left Dave completely astonished, but it gave him the feeling and conviction that he was able to continue with his life, possibly through the act of forgiveness. Dave further stated that he had a long afterglow while in the hospital and never felt unsafe during his experience. What is more, Dave has developed a so-called MDMA mindset that he can access at will at any time during the day. This has finally brought him warmth and calmness after decades. Dave stated that “it is the best treatment I have had in almost 40 years.” But he is also “frustrated by the lack of governmental acceptance and approval”, as both he, and many others suffering from PTSD, have improved so dramatically after MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. Dave concluded his testimony by saying that stating that “this could be the most profound transformation in healthcare.” There are many profound stories out there like Dave’s that almost seem too good to be true. Right after this testimony, the audience was confronted with the dark side of psychedelics.

Jules Evans, an academic philosopher and director of Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project, is aware of the ongoing psychedelic renaissance and many benefits associated with it, but he also acknowledges the various difficulties and challenges associated with psychedelics. This is based on his own personal experience and research with psychedelics. For instance, Evans had his own bad trip at 18 years and developed PTSD and social anxiety after taking LSD with some of his friends. Fortunately, Evans got better after receiving cognitive-behavioural therapy. Evans further gave notice of a bigger survey (n = 10,836) conducted by ICEERS that collected data from more than 50 countries to assess the adverse events following the use of ayahuasca. This survey showed that there is a high rate of adverse physical effects, primarily vomiting (69.9%), and adverse mental health effects (55.9%) in the weeks or months following consumption. Yet, the authors of this paper also concluded that these experiences “are not generally severe, and most ayahuasca ceremony attendees continue to attend ceremonies, suggesting they perceive the benefits as outweighing any adverse effects.” More recently, Evans has conducted an interview study with 30 individuals after a psilocybin truffle retreat in the Netherlands and was able to show that 30% of individuals experienced challenging experiences.

Our very own Joost Breeksema also acknowledges in a recent review of 44 articles that psychedelics are associated with adverse events and that they are probably underreported due to a lack of systematic assessment and sample selection. Yet, this review also stated that challenging experiences can sometimes be therapeutically meaningful and that we should focus on “disentangling truly adverse events from potentially beneficial effects in order to improve our understanding of psychedelic treatments.”

Moving Forward

The amount of knowledge gaps discussed during the conference are manyfold. One message seemed to reverberate through the two days of the ENCP conference – and that is we simply need more research. We need larger studies with more participants and longer follow-ups. Besides this, I went over and compared all my notes from the conference and was able to distil the most prominent knowledge gaps consistent among both speakers and attendees. Here are the three key knowledge that can help move the psychedelic research forward in the upcoming years.

First and foremost, there is the question whether subjective effects are truly responsible for the therapeutic efficacy of psychedelics. Novel psychoplastogens as tabernanthalog developed by David Olsen seem to negate this view. However, the work that has been done so far is based entirely on animal research paradigms, which Emma Robinson pointed out lacks translational validity in humans. It would be interesting to see Olsen and Robinson pair up in order to assess whether the findings still hold up when rodents receive the non-hallucinogenic compound tabernanthalog and are put to the ‘affective bias test’.

Second, our understanding of the neurobiology of psychedelics remains somewhat underdeveloped. Katrin Preller signified this during her talk by pointing out the degree of inter-individual heterogeneity. To reconcile this, we simply need to conduct more studies that are longer and more complex. The multimodal brain imaging study conducted by Imperial College London that assessed the effects of psychedelics before, during, and after a DMT experience using both EEG and fMRI serves as a perfect example of such a study. And we need lots of it.

Third, the investigation of drug-drug interactions, be it the antidepressant escitalopram, bupropion, or ketanserin, show their utility for potential harm reduction and how through pharmacological interaction we could improve psychedelic therapy and outcome. This could have huge implications for how we conduct psychedelic therapy

The Hype is Real

After the ECNP conference, I can confidently say that “the hype is real” in the field of psychedelic research. Even though the legendary hip-hop group Public Enemy stated that we should not believe the hype, I have garnered only more hype in the form of inspiration, enthusiasm, and realistic optimism. The future for psychedelic research looks promising with lots of different topics to explore and it is truly great that European regulatory committees as the SAWP are involved to help establish rigorous and robust scientific research that will only affirm the validity and credibility of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. And we are very fortunate that all this is accompanied by a healthy dose of scepticism by the likes of individuals as Jules Evans. Ultimately, there is enough balance of both yin and yang that can help move the field forward and I am proud to be a part of it.

There were other speakers that I did not mention as this was beyond the scope of this blog post. Despite this, I wanted to clarify here that their talks were greatly appreciated during the conference and have listed their names and credentials down below.

- David E. Nichols, Adjunct Professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the Purdue University College of Pharmacy. Nichols talked about the basic pharmacology of psychedelics.

- Tomas Palenicek, head of the Psychedelic Research Centre at National Institute of Mental Health, Czech Republic. Palenicek talked about how music genres like psytrance and classic music seem to show the most benefit during psychedelic therapy.

- Jan Raemakers, Professor of Psychopharmacology and Behavioral Toxicology at Maastricht University. Raemakers talked about the feasibility of 5-MeO-DMT in healthy volunteers and individuals with treatment-resistant depression.

- David Erritzoe, Clinical Senior Lecturer and Consultant Psychiatrist at Imperial College London and in CNWL Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust. Erritzoe talked about psilocybin therapy for depression.

- Drummond McCulloch is a PhD who studies the effects of psychedelic drugs on the brain using PET and MR imaging at the Neurobiology Research Unit in Copenhagen. His talk included qualitative data analyses of a clinical trial showing how individuals come more connected to their self, others, and the environment.

- Jaskaran B. Singh, Psychiatry Franchise head at Neurocrine Biosciences. His talk consisted of Industry aspects, precompetitive questions, experience from a related area (esketamine).

- Tiffany Farchione, Director of the Division of Psychiatry in the Office of Neuroscience at FDA. Tiffany’s talk includes regulatory perspectives of the Food and Drug Administration.