Psychedelic drug users throughout the ages have described their experiences as mind-expanding. They might be surprised, therefore, to hear that psilocybin – the active ingredient in magic mushrooms – actually decreases blood flow as well as connectivity between important areas of the brain that control perception and cognition.

The same areas can be overactive in people who suffer from depression, making the drug a potential treatment option for the condition. The study is the first time that psilocybin’s effects have been measured with fMRI, and the first experiment involving a hallucinogenic drug and human participants in the UK for decades.

Robin Carhart-Harris at Imperial College London and colleagues recruited 30 volunteers who agreed to be injected with psilocybin and have their brain scanned using fMRI.

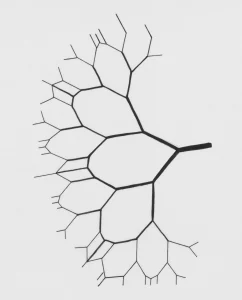

Low flow

Less blood flow was seen in the brain regions known as the thalamus, the posterior cingulate and the medial prefrontal cortex. “Seeing a decrease was surprising. We thought profound experience equalled more activity, but this formula is clearly too simplistic,” says Carhart-Harris. “We didn’t see an increase in any regions,” he says.

Decreases in connectivity were also observed, such as between the hippocampus and the posterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex.

“Under psilocybin you see a relative decrease in ‘talk’ between the hippocampus and these cortical hub regions,” says Carhart-Harris. “Changes in function in the posterior cingulate in particular are associated with changes in consciousness.”

Mood swing

Psilocybin has a similar chemical structure to serotonin – a hormone involved in regulating mood – and therefore binds to serotonin receptors on nerve cells in the brain. The drug may have therapeutic potential because the serotonin system is also a target for existing antidepressants.

A study last year by Charles Grob at the University of California, Los Angeles, showed that people with end-stage cancer had significantly less anxiety and better mood after receiving psilocybin.

Franz Vollenweider, who works in a similar field at the Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, says that the immediate effects of psilocybin are not as important for clinical benefit as the longer-term effects. That’s because psilocybin increases the expression of genes and signalling proteins associated with nerve growth and connectivity, he says: “We think that the antidepressant effects of psilocybin may be due to a possible increase of factors that activate long-term neuroplasticity.”

Carhart-Harris presented his work at the Breaking Convention conference at the University of Kent in Canterbury, UK, last week.