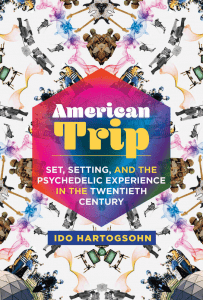

Ido Hartogsohn is one of the first and few researchers to focus on psychedelic research from a social technological perspective. The assistant professor from the Science, Technology and Society program at Bar Ilan University in Israel has just published a new book called American Trip, in which he explores how the social conditions of the 1960s shaped the American psychedelic experience itself.

In his recently published book he inquires how the LSD experience was shaped by the social conditions and predominant values of the fifties and sixties, portraying LSD as a “psychopharmacological chameleon” dependent on culture. With this move, he expands the traditional meaning of set & setting in psychedelic therapy to include the broader contexts in which these substances are used. He calls this the “collective set and setting”: the broader cultural and social contexts in which these substances are used.

His work brings a sociological perspective that invites us to rethink psychedelic drugs beyond their mere pharmacological properties.

How do your views challenge conventional understandings of drug effects in pharmacology?

One of the defining ideas of pharmacology is an often implicit notion which scholar Richard DeGrandpre termed pharmacologicalism: the assumption that a drug is exclusively defined by its inherent pharmacological qualities – that it has one type of discrete effect independent of any variables.

The closer we look at the effects of drugs, the more we see that they do not work like that at all. The effects of drugs, not just psychedelics, can change radically depending on the social and physical environment.

Think of the example of US soldiers returning from Vietnam in the 1970s. The American army tried numerous plots to help these soldiers kick their heroin habit while they were in Vietnam, but all of these ultimately failed. Then, as the soldiers returned home, suddenly 90% of them were able to kick the habit spontaneously, without going through any kind of treatment.

Once the setting changed we could see that – even in the case of the supposedly most rigid, inflexible and essentially physical drugs, effects were highly dependent on the set and setting of use.

This is something that pharmacological discourse has been reluctant to acknowledge over the years. It makes sense because once you acknowledge that, it complicates drug trials and discussions around drugs. It forces us to think about not only the very chemical product that we give to patients but how we give it to them and the whole clinical environment. It also forces us to forsake these very naive ideas of drugs as magic bullets that have one specific effect and one specific and highly discrete application.

The cultural malleability of psychedelic experiences has great implications for drug policy. How do you think that prohibitionism and anti-drug propaganda could have infiltrated the very experiences of psychedelic users?

There is this classic study by the sociologist Richard Bunce about the dramatic increase of bad trips at the end of the 1960s as authorities were pushing different scare theories such as the idea that LSD creates chromosome damage or that it will “fry your brain”. All of that stuff was completely debunked later on but once you have these ideas percolating inside the culture, they can easily penetrate people’s experiences. Given this type of ‘collective set and setting’, levels of paranoia shot up among users. Experiences that could be interpreted as quite benign and pleasant turned in a way that is very scary.

This kind of effect is something anthropological literature was predicting already a decade earlier. In the late 1950s, anthropologist Anthony Wallace argued that psychedelic users in the West were more liable to have negative experiences than those that had them in traditional or indigenous societies. Societies, like in the West, that conceive of hallucinations as something that is inherently dangerous and meaningless increase the chance for harmful experiences.

This kind of effect is something anthropological literature was predicting already a decade earlier. In the late 1950s, anthropologist Anthony Wallace argued that psychedelic users in the West were more liable to have negative experiences than those that had them in traditional or indigenous societies. Societies, like in the West, that conceive of hallucinations as something that is inherently dangerous and meaningless increase the chance for harmful experiences.

I believe that there have been so many psychedelic trips gone awry as a result of prohibition; so much mental energy that has been squandered; so many positive experiences of users over the years that took a bad turn when they for example encountered police during a trip or were somehow perturbed by the ideology, propaganda and policy of the war on drugs.

So, if we are to take a harm reduction approach to drug use, what can we do to improve the collective set & setting of psychedelic use today and in the future?

One of the most beautiful things that is happening today in the so-called “psychedelic renaissance” is this burgeoning culture of set and setting: the growing awareness of the importance of preparation, intention, and integration – of knowing your substance, your set and your setting.

Psychedelic users today are much more “psychedelically literate” than the ones in the 1960s, and that’s a result of a very rich culture of discourse and practice informed by the idea of set and setting. So we now have safezone organizations which provide for example psychedelic first aid or peer support in festivals like Burning Man or Boom; we have online trip-sitting services run by volunteers; books and websites guiding about the principles of safe and transformative psychedelic voyaging, and there are more and more studies that aim to study how set and setting work.

These are all very hopeful signs that the appreciation of the importance of set and setting is more and more widely recognized in the field of psychedelics, for the broader community as well as for the clinical community.

Governments that want to approach this subject from a progressive perspective need to realize that outmoded, ideologically rigid approaches to drug use fail their citizenry and ultimately the entire society. Governments are betraying their role when they prosecute users. What they should be doing is helping the general public get the know-how, the information and the resources that could help minimize harmful experiences and maximize the potential for safe, positive and meaningful experiences.

You argue that the placebo effect can be understood as a form of meaning response, in which clinical improvement follows from the mere manipulation of meaningful cues in the therapeutic process. Accordingly, the meaning-enhancing properties of psychedelics turn them into some kind of “super-placebo”. What would be the consequences of this reconceptualization for current clinical trials with psychedelics and their placebo-control methodologies?

Over the years the pharmaceutical industry has been invested in the attempt to minimize or eliminate placebo effects. If you are selling a drug like they are, you probably want to give a decisive answer about its effects. But once [the placebo-effect] enters the picture, it appears much more uncertain what the drug actually accomplishes by itself.

After clinical trials, we see that the efficacy of that same drug diminishes from year to year of use in the market, or from culture to culture, because of the changes in the placebo response and in the meaning attributed to the drug. We can therefore see that drug effects are much more fluid than we are led to believe.

Medical anthropologist Daniel Moerman draws our attention to the fact that placebo response can more intelligibly be conceived as just meaning response. When you bring this insight into contact with the field of psychedelics something quite interesting emerges, because one of the main effects of psychedelics is to enhance the perception of meaning.

This then raises the possibility that psychedelics may enhance the placebo response by enhancing our perception of meaning. This potential of psychedelics to enhance placebo really holds a valuable alternative to the classic pharmacological model and an opportunity to think about how meaning intervenes in therapeutic processes.

I don’t think that we are about to see the end of the blind trials paradigm anytime soon. But rather than looking for an objective response to a drug and leaving it at that, we would achieve better results if we focused our energy at examining the nexus between drug, set and setting, to optimize the overall therapeutic process in a way that transcends commonplace flat and impoverished conceptions of the drug responses.

You have approached psychedelics from a science and technology studies (STS) perspective. What has that taught you?

When you look at LSD and psychedelics in general, you have a technology whose effects are highly malleable. Depending on the set and setting, a hallucinogenic agent like LSD can be a psychotomimetic (psychosis mimicking) and it can be therapeutic. It can be anxiety-inducing and it can be mentally soothing.

The effects of LSD are so radically transformed in relation with user’s mindsets and settings that you could argue that LSD, as a technological artifact, is recreated every time it is used. This recognition leads to the concept of psychedelics as a technology that is culturally and socially constructed in a radical way.

One of the main takeaways that I am trying to convey in my book is the idea of a “psychedelic technology”. Going back to the very meaning of the word psychedelic as “mind-manifesting”, the category of “psychedelic technology” would then refer to technology that is shaped in accordance with the mind-set and the environment (hence the idea of an ecodelic) of the user. This is an interesting way to think about technology that is a radical extension of the social constructivist way to think about technologies in the field of STS.

My perspective on psychedelics later shifted to the STS idea of co-production, the question of how the effects of LSD and other psychedelics are shaped and formed by social values, norms and conditions, and how LSD and other psychedelics simultaneously bring about changes in social and cultural movements creating a kind of positive feedback loop, an idea that I explore in my book.

What will be the major takeaways that potential attendees of ICPR might expect from your talk or about your book?

One of the main things my book tries to do is to really expand our understanding of set and setting in order to transcend that more narrowly defined, individualized concept of set and setting. I think the book makes clear that no factor in the individual, specific or concrete set and setting of a psychedelic experience is independent of the larger social and cultural picture, and so I try to answer the question how our collective historical and social forces worked to shape the psychedelic experience in the West since the 1960s and to this day.

Ido Hartogsohn talk at ICPR 2020 will explore the relationship between set and setting, meaning-enhancement and placebo as a central axis on which the psychedelic experience can be interpreted and understood.

In his recently published book he inquires how the LSD experience was shaped by the social conditions and predominant values of the fifties and sixties, portraying LSD as a “psychopharmacological chameleon” dependent on culture. With this move, he expands the traditional meaning of set & setting in psychedelic therapy to include the broader contexts in which these substances are used. He calls this the “collective set and setting”: the broader cultural and social contexts in which these substances are used.

His work brings a sociological perspective that invites us to rethink psychedelic drugs beyond their mere pharmacological properties.

How do your views challenge conventional understandings of drug effects in pharmacology?

One of the defining ideas of pharmacology is an often implicit notion which scholar Richard DeGrandpre termed pharmacologicalism: the assumption that a drug is exclusively defined by its inherent pharmacological qualities – that it has one type of discrete effect independent of any variables.

The closer we look at the effects of drugs, the more we see that they do not work like that at all. The effects of drugs, not just psychedelics, can change radically depending on the social and physical environment.

Think of the example of US soldiers returning from Vietnam in the 1970s. The American army tried numerous plots to help these soldiers kick their heroin habit while they were in Vietnam, but all of these ultimately failed. Then, as the soldiers returned home, suddenly 90% of them were able to kick the habit spontaneously, without going through any kind of treatment.

Once the setting changed we could see that – even in the case of the supposedly most rigid, inflexible and essentially physical drugs, effects were highly dependent on the set and setting of use.

This is something that pharmacological discourse has been reluctant to acknowledge over the years. It makes sense because once you acknowledge that, it complicates drug trials and discussions around drugs. It forces us to think about not only the very chemical product that we give to patients but how we give it to them and the whole clinical environment. It also forces us to forsake these very naive ideas of drugs as magic bullets that have one specific effect and one specific and highly discrete application.

The cultural malleability of psychedelic experiences has great implications for drug policy. How do you think that prohibitionism and anti-drug propaganda could have infiltrated the very experiences of psychedelic users?

There is this classic study by the sociologist Richard Bunce about the dramatic increase of bad trips at the end of the 1960s as authorities were pushing different scare theories such as the idea that LSD creates chromosome damage or that it will “fry your brain”. All of that stuff was completely debunked later on but once you have these ideas percolating inside the culture, they can easily penetrate people’s experiences. Given this type of ‘collective set and setting’, levels of paranoia shot up among users. Experiences that could be interpreted as quite benign and pleasant turned in a way that is very scary.

This kind of effect is something anthropological literature was predicting already a decade earlier. In the late 1950s, anthropologist Anthony Wallace argued that psychedelic users in the West were more liable to have negative experiences than those that had them in traditional or indigenous societies. Societies, like in the West, that conceive of hallucinations as something that is inherently dangerous and meaningless increase the chance for harmful experiences.

This kind of effect is something anthropological literature was predicting already a decade earlier. In the late 1950s, anthropologist Anthony Wallace argued that psychedelic users in the West were more liable to have negative experiences than those that had them in traditional or indigenous societies. Societies, like in the West, that conceive of hallucinations as something that is inherently dangerous and meaningless increase the chance for harmful experiences.I believe that there have been so many psychedelic trips gone awry as a result of prohibition; so much mental energy that has been squandered; so many positive experiences of users over the years that took a bad turn when they for example encountered police during a trip or were somehow perturbed by the ideology, propaganda and policy of the war on drugs.

So, if we are to take a harm reduction approach to drug use, what can we do to improve the collective set & setting of psychedelic use today and in the future?

One of the most beautiful things that is happening today in the so-called “psychedelic renaissance” is this burgeoning culture of set and setting: the growing awareness of the importance of preparation, intention, and integration – of knowing your substance, your set and your setting.

Psychedelic users today are much more “psychedelically literate” than the ones in the 1960s, and that’s a result of a very rich culture of discourse and practice informed by the idea of set and setting. So we now have safezone organizations which provide for example psychedelic first aid or peer support in festivals like Burning Man or Boom; we have online trip-sitting services run by volunteers; books and websites guiding about the principles of safe and transformative psychedelic voyaging, and there are more and more studies that aim to study how set and setting work.

These are all very hopeful signs that the appreciation of the importance of set and setting is more and more widely recognized in the field of psychedelics, for the broader community as well as for the clinical community.

Governments that want to approach this subject from a progressive perspective need to realize that outmoded, ideologically rigid approaches to drug use fail their citizenry and ultimately the entire society. Governments are betraying their role when they prosecute users. What they should be doing is helping the general public get the know-how, the information and the resources that could help minimize harmful experiences and maximize the potential for safe, positive and meaningful experiences.

You argue that the placebo effect can be understood as a form of meaning response, in which clinical improvement follows from the mere manipulation of meaningful cues in the therapeutic process. Accordingly, the meaning-enhancing properties of psychedelics turn them into some kind of “super-placebo”. What would be the consequences of this reconceptualization for current clinical trials with psychedelics and their placebo-control methodologies?

Over the years the pharmaceutical industry has been invested in the attempt to minimize or eliminate placebo effects. If you are selling a drug like they are, you probably want to give a decisive answer about its effects. But once [the placebo-effect] enters the picture, it appears much more uncertain what the drug actually accomplishes by itself.

After clinical trials, we see that the efficacy of that same drug diminishes from year to year of use in the market, or from culture to culture, because of the changes in the placebo response and in the meaning attributed to the drug. We can therefore see that drug effects are much more fluid than we are led to believe.

Medical anthropologist Daniel Moerman draws our attention to the fact that placebo response can more intelligibly be conceived as just meaning response. When you bring this insight into contact with the field of psychedelics something quite interesting emerges, because one of the main effects of psychedelics is to enhance the perception of meaning.

This then raises the possibility that psychedelics may enhance the placebo response by enhancing our perception of meaning. This potential of psychedelics to enhance placebo really holds a valuable alternative to the classic pharmacological model and an opportunity to think about how meaning intervenes in therapeutic processes.

I don’t think that we are about to see the end of the blind trials paradigm anytime soon. But rather than looking for an objective response to a drug and leaving it at that, we would achieve better results if we focused our energy at examining the nexus between drug, set and setting, to optimize the overall therapeutic process in a way that transcends commonplace flat and impoverished conceptions of the drug responses.

You have approached psychedelics from a science and technology studies (STS) perspective. What has that taught you?

When you look at LSD and psychedelics in general, you have a technology whose effects are highly malleable. Depending on the set and setting, a hallucinogenic agent like LSD can be a psychotomimetic (psychosis mimicking) and it can be therapeutic. It can be anxiety-inducing and it can be mentally soothing.

The effects of LSD are so radically transformed in relation with user’s mindsets and settings that you could argue that LSD, as a technological artifact, is recreated every time it is used. This recognition leads to the concept of psychedelics as a technology that is culturally and socially constructed in a radical way.

One of the main takeaways that I am trying to convey in my book is the idea of a “psychedelic technology”. Going back to the very meaning of the word psychedelic as “mind-manifesting”, the category of “psychedelic technology” would then refer to technology that is shaped in accordance with the mind-set and the environment (hence the idea of an ecodelic) of the user. This is an interesting way to think about technology that is a radical extension of the social constructivist way to think about technologies in the field of STS.

My perspective on psychedelics later shifted to the STS idea of co-production, the question of how the effects of LSD and other psychedelics are shaped and formed by social values, norms and conditions, and how LSD and other psychedelics simultaneously bring about changes in social and cultural movements creating a kind of positive feedback loop, an idea that I explore in my book.

What will be the major takeaways that potential attendees of ICPR might expect from your talk or about your book?

One of the main things my book tries to do is to really expand our understanding of set and setting in order to transcend that more narrowly defined, individualized concept of set and setting. I think the book makes clear that no factor in the individual, specific or concrete set and setting of a psychedelic experience is independent of the larger social and cultural picture, and so I try to answer the question how our collective historical and social forces worked to shape the psychedelic experience in the West since the 1960s and to this day.

Ido Hartogsohn talk at ICPR 2020 will explore the relationship between set and setting, meaning-enhancement and placebo as a central axis on which the psychedelic experience can be interpreted and understood.